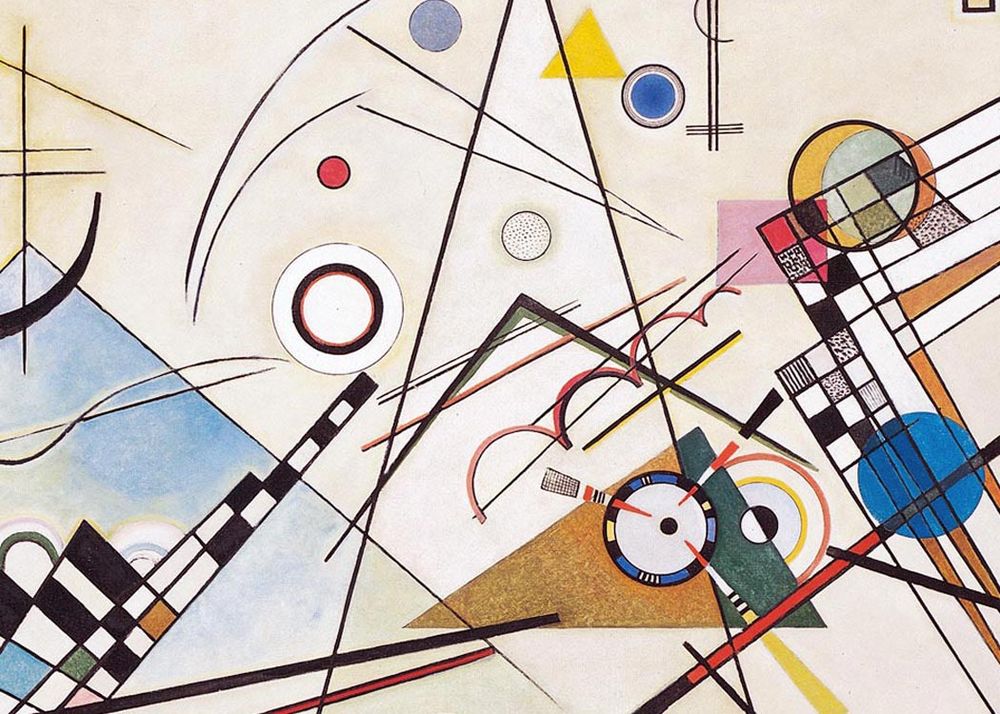

In the 1920s a number of French designers promoted a style that made ornament modern. They turned their backs on traditional classical and Gothic forms of architectural decoration, drawing inspiration from sources as distant as ancient Egypt to combine vivid color and pattern with modern lines. The result was Art Deco, and it had a huge impact in the period between the two world wars.

In the modern architecture of the 1920s and 1930s the most ubiquitous way of working was what became known as the International Style (see The International Style) or International Modernism—the way of building in which form was said to follow function, materials (concrete, steel and glass) were enjoyed for their intrinsic qualities and ornament was virtually banished. But there was also a contrary tendency, a style of architecture and decoration in which modern materials were used in conjunction with bold and often exotic geometric ornament. This style has come to be known as Art Deco.

A formative exhibition

Art Deco began in France under the auspices of a group of French artists and designers called the Société des artistes décorateurs. In 1925 the society organized an exhibition in Paris, the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes. This exhibition included a range of designs and styles—Russian constructivism was represented, for example, as were the pared-down designs of men such as Le Corbusier, which were key to International Modernism. But at the exhibition’s heart was a variety of highly decorative, luxury objects—the items that first defined the Art Deco style—the name of which derives from the words Arts Décoratifs in the exhibition title.

Art Deco style was defined by the decoration used on the object and this had an eclectic range of sources: a type of stylized, streamlined classicism; the use of geometrical patterns to produce crystal-like shapes; decorative motifs drawn from ancient Egyptian, Aztec and African art; and the use of splashes of bright color or rich gilding in combination with pale backgrounds. Stylized fountains, sunbursts and lightning flashes were popular ornamental patterns; polished steel and aluminum and inlaid woods were prominent materials.

From decoration to architecture

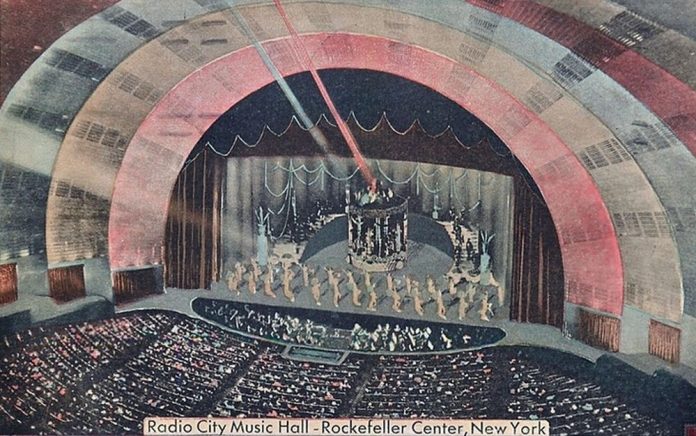

Art Deco provides a popular style for a host of decorative items from pottery and table lamps to statuettes, often featuring glamorous women—clothed or naked—on striking geometrical bases. The style also caught on in architecture in the 1920s and 1930s. Its decorative flair made it attractive for houses, hotels and commercial buildings—the two most famous early New York skyscrapers—the Empire State and Chrysler buildings—are both examples of Art Deco.

“Cosmetic Deco and moderne façades brought a face-lift to Main Street America …” Stephen Sennott, Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century Architecture

Industrialists liked to use the style for their factories, sensing that the decorative style, which could transfer with ease from package design to architecture, enabled them to display their brand on a large scale. Cinema owners, too, found Art Deco, with its strong lines and decorative flair, ideal for their buildings.

Streamline moderne

The streamline moderne style is a cousin of Art Deco that emerged in the 1930s. Inspired in part by the long, low, curvaceous lines of streamlined automobiles such as the 1930s Chrysler Airflow, it applied the aesthetics of streamlining to buildings. Streamline moderne buildings often have a horizontal, ground-hugging emphasis. They make prominent use of horizontal accents, such as long strips of windows—often metal-framed with plenty of horizontal glazing bars—and balconies with long rails like those on ocean liners. Unlike Art Deco buildings, which are all sharp angles and crystalline forms, streamline moderne buildings also incorporate curves—round, porthole-like windows, circular electric light fittings and curving corners; sometimes even bay or end windows that turn the corner with a curved pane of glass.

Deco around the world

And Art Deco did spread widely around the world. Cities that were being aggressively developed in the 1930s were hotbeds of the style—there are still many Art Deco buildings in Miami, Havana, Cuba, and the larger towns of Indonesia. And the town of Napier, New Zealand, severely damaged in an earthquake in 1931, was largely rebuilt in the style. Its concentration of Art Deco buildings is still famous.

A popular style

Thanks to the luxurious cinemas and hotels Art Deco had a popular following. But it was rather frowned on by many architects, who preferred the more rigorous “form follows function” aesthetic of International Modernism. For modernist architects and many architectural critics, Art Deco was an ephemeral style, fit more for ashtrays and statuettes than for buildings. But what put an end to the fashion for Art Deco was the beginning of the Second World War, which in 1939 imposed a virtual stop on building in many parts of the world.

Naming the style

The term Art Deco is now very familiar. It comes from the title of the 1925 Paris exhibition, the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, that introduced the style. But the term was not much used when the style was fashionable—people originally referred to it as the Style Moderne, or simply as Moderne. In the 1960s there was a revival of interest in the style, and writer and critic Bevis Hillier published a book Art Deco of the 20s and 30s, which popularized this name, leaving the term Moderne for use in connection with the streamlined, automobile-inspired style that developed shortly after Art Deco itself.

After the war ended, and planners and architects began to begin the vast rebuilding programs that were needed, they looked to the more sober modernist style. Art Deco survived in the interior decorations schemes of a few new restaurants and department stores, but was mostly seen as a memory of earlier, more frivolous times.