Mass car ownership and the increased traffic it brought posed a major challenge to architects and planners. For decades, the obvious solution seemed to be to segregate pedestrians and traffic to make people safer and more comfortable and to allow cars to move quickly. But taken to its logical conclusion in the 1950s and 1960s, the idea proved a disastrous failure.

The garden city movement of the late 19th century is remembered for the way it encouraged the greening of the city (see Garden city). But another major part of the garden city idea was zoning—each part of the city had a specific purpose (housing, shopping, industry, parks and so on) and the zones were linked by a carefully planned network of major and minor roads.

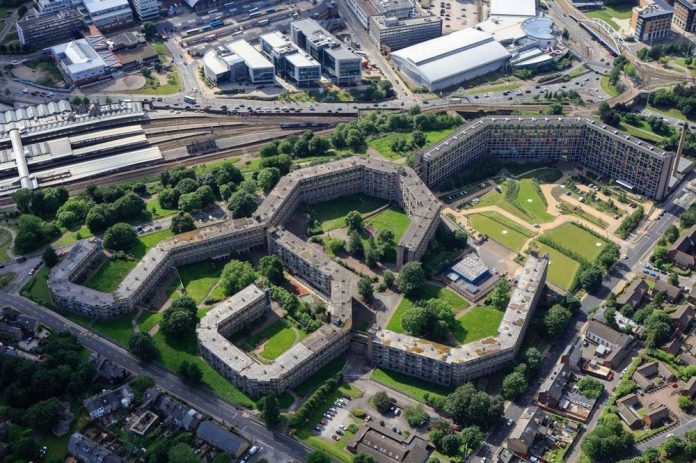

Radburn planning

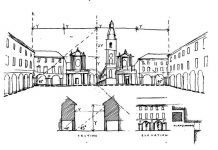

The city planners of the 20th century took this idea of zoning still further, and applied it not only to the functions of the parts of the town, but also to the transport arteries. The most famous pioneering example of this was the town of Radburn, New Jersey, which was founded in 1929 with a plan specifically tailored to the age of motor transport.

For Radburn’s planners the key was to separate cars and pedestrians. They developed a system of pedestrian paths and used bridges and underpasses to allow these to cross the motor roads. The aim was to increase pedestrian safety and also to keep traffic flowing and the town seemed to answer for the first time the question of how urban centers could deal with the car.

Radburn set other trends in planning, too. The residential areas of the town were laid out in “super blocks,” each of which contained a network of culs-de-sac that gave streets a feeling of seclusion and privacy. In addition, local access roads were separated form the main through routes to help the traffic flow and make navigation easier.

A delayed reaction

This type of planning was inspiring, and had Radburn not been founded in a time of economic depression, might have caught on quickly. As it was, the influence of Radburn came late, but spread more widely. Some of its principles— especially the hierarchy of roads and pedestrian routes—were adopted by the modernist group CIAM, and they began to appear in modernist plans after the Second World War. Chandigarh, the capital of the Punjab, planned by Albert Mayer, Matthew Nowicki and Le Corbusier, was a famous example.

So, promoted by modernist architects and in response to increasing car ownership and goods traffic, segregated planning became commonplace in the 1950s and 1960s. It seemed logical and safe to separate pedestrians and cars, and architects saw opportunities to make new types of buildings based on the idea of keeping cars and pedestrians separate.

“… claustrophobic walk-ups or corridors were rejected in favor of 12ft-wide ‘streets in the sky’ … The architects thought they had solved the problems of modernist housing.” Owen Hatherley, writing in the Guardian

Enter the walkway

The result was a multitude of large building projects—from housing schemes to public buildings—in which access was via pedestrian walkways. Such schemes seemed exciting, because they offered safe, traffic-free routes as well as interesting new urban spaces in which pedestrians could walk, gather, shop and even sit at café tables, in comfort. Away from traffic noise and fumes, life would be easier. And separate access roads to garages and parking spaces were provided, usually at the back of the buildings out of sight and earshot of all the pedestrian activity.

The shopping mall

This type of building in which pedestrians are sheltered in comfort and cars are parked conveniently nearby has flourished commercially in the last 50 years. But although shopping malls have their architectural ancestry in the elegant arcades and markets of the 19th century, most are architecturally undistinguished. In addition they have been widely criticized for attracting stores and shoppers away from town centers, leading to economic decline in some inner cities.

Combined with the bright new world of concrete-and-glass architecture that was the fashion in the post-war period, this type of planning seemed to offer a new utopia—a world in which people could benefit from mass car ownership without being overwhelmed by it. It also seemed to offer a way of “humanizing” monolithic housing blocks by providing pedestrian “streets in the sky,” where people could meet and talk as they walked to their front doors.

Unforeseen consequences

Mostly, however, the concept did not work. Streets in the sky became the haunt of muggers and raised walkways were too often bleak and windswept. Concrete buildings turned from shining white to dirty, weathered gray. Even high-profile schemes, such as the pedestrian walkways giving access to the arts venues on London’s South Bank, looked lackluster a few years after construction.

In many cases there was only one solution to the toxic combination of poorly maintained concrete buildings and discredited segregated planning: demolish the lot and start again. So by the 1990s, many 1960s’ blocks and walkways had been reduced to rubble, having had a far shorter life than the 19th-century terraced houses that many of them had replaced.

Conserve or demolish?

Segregated planning has a long history, and early examples of pedestrian walkways and bridges like the covered bridge in Lewisburg, West Virginia (below), are now valued by conservationists. Some of the housing schemes of the 1960s are now controversial because they are seen by some architects and critics as representing the best of 1960s’ architecture, although they have deteriorated structurally and often socially. This leaves planners in a dilemma: do they give permission for demolition or spend vast amounts of money restoring buildings that did not work the first time around? At the huge Park Hill estate in Sheffield, a listed brutalist scheme completed in 1961 with “streets in the sky,” a restoration is underway. The Robin Hood Gardens estate (completed in 1972) in East London, by contrast, has not been listed and is threatened with demolition.