The way we have looked at historical buildings has changed greatly over the past 150 years. From being all but ignored by the authorities, historic architecture became a central part of our “heritage” in a movement that led to much more rigorous preservation, but which was also sometimes connected to a false or nostalgic view of the past.

Organizations such as the SPAB (see Conservation) did ground-breaking work, showing the best ways to repair and maintain old buildings. But these were voluntary organizations—it was still up to owners to carry works out in the best way. Not all of them did this, and throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries many important old buildings in Britain and in other countries were demolished.

Protection by law

One solution was to introduce legal protection for important monuments or buildings. Greece was a pioneer in this area. The country was the first to pass a law to protect ancient monuments, in 1834. The Danes followed suit and, in the 19th century, Germany, Holland, Italy, Sweden and the USA also started to bring in legislation to protect important historical structures. France, too, long after Victor Hugo’s cry to “still the hammer that is mutilating the face of the country,” passed a Historical Monuments Act in 1887.

Britain as well acquired an Ancient Monuments Act in the 1880s. Its remit, however, was quite restricted—to such monuments as earthworks, burial mounds, stone circles, and ruined abbeys.

Under threat

In 1893 Britain responded to appeals to preserve and protect both ancient buildings and natural scenery through another voluntary body—the National Trust. Set up to acquire and maintain “places of interest or beauty,” it concentrated at first on landscape and scenery, but later acquired many historic buildings and showed the way to similar organizations in other parts of the world.

Heritage and war

Meanwhile the huge economic changes in the early 20th century had a profound impact on old buildings. After the First World War, the owners of many historic houses could no longer afford to run them, and hundreds were demolished. By the eve of the Second World War, however, many were mourning the loss of those buildings, and regretting that much of Britain’s architectural heritage had been thrown away.

The term “heritage” began to become widespread at this time and, when war came, people saw themselves as defending from further destruction the historical birthright of Britain. Heritage became key to national identity—a fact that was highlighted in books such as the “Face of Britain” (on regions of Britain) and “British Heritage” series published by Batsford. Other publications, such as the Shell Guides to English counties, did more to present heritage to a wider public.

“The notion of ‘heritage’ has been broadened and indeed transformed to take in not only the ivied church and village green but also the terraced street, the railway cottages, the covered market and even the city slum …” Raphael Samuel, Theatres of Memory

Listing buildings

Wartime also saw the birth of Britain’s building listing system, in which historic buildings are graded, listed and protected by law. The system did not come soon enough to save yet more country houses demolished in the 1950s, but has since provided an effective way of protecting historic and architecturally important buildings. The growth of still more voluntary groups—local civic societies and national specialist groups, such as the Georgian Group and Victorian Society, for example—did more for the cause of old buildings. English Heritage, the government quango set up both to advise government on conservation matters and act as custodian of many state-owned sites, made a major contribution, too.

Listed buildings

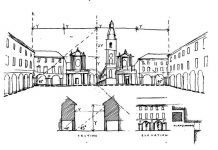

In 1940s Britain buildings inspectors set out to make the first lists of the country’s important and historic buildings. So that they knew which structures to list for protection, they followed a series of guidelines about the types of buildings that were of interest.

- Major examples of the work of specific architects.

- Buildings that typify a specific style of architecture.

- Structures that are interesting because they have altered organically over the years, displaying a hotchpotch of styles.

- Follies and other “bizarre buildings.”

- Structures that evoke the lives of past generations, including important industrial sites.

- Buildings associated with a particular historical figure.

- Buildings that, while not important in themselves, form part of a major historical group of structures.

The rise of nostalgia

But there was another side to the preservation movement, sometimes seen as less beneficial. The work of conservationists, the National Trust, country house owners throwing open their doors and setting up wildlife parks in their grounds, of historically minded entrepreneurs and canny travel companies also turned heritage into an industry. Feeding on a nostalgia for a partly fictional past, it fed visitors a partial view of history.

Nostalgia ruled, and critics mourned the fact that Britain and other countries were in danger of turning into historic theme parks. During a period when manufacturing industries in Western Europe were closing or moving to Asia, it seemed to some that making money from a false image of a rosy past was no substitute for an economy that had once produced real goods. Others, including the cultural critic Robert Hewison, pointed to the deadening effect on culture that nostalgia could have.

A changing focus

One corrective to this nostalgia was a welcome willingness to change the focus of history. English Heritage and the National Trust increasingly preserved ordinary buildings, told the stories of staff and servants when they opened big houses to the public and displayed the findings of industrial archaeologists about mines, mills and factory life.

These more recent changes have led many people to be more questioning about what the heritage industry and the buildings in its care tell us. And visitors are now better informed about the architecture of the past and its social setting than ever. But neither the nostalgia, nor the proliferation of heritage “products,” from souvenir shops to nostalgia, has entirely gone away.