Our movement through towns is normally along streets and roads, and hence our perception of the quality of place is shaped by what we see from them. Anybody intent upon exploring cities through the freehand sketch should, therefore, concentrate upon the routes people normally take. These vary from grand streets to alleyways and pedestrian footpaths, and each has its distinctive character. The different types of city route can be categorised as follows:

- street: a relatively formal route lined by continuous frontages of buildings;

- boulevard: a grander version of the street, often containing trees planted in parallel rows, and sometimes with a central reservation;

- road: an informal car-dominated route generally of a suburban nature;

- lane: an access route often serving the rear of properties and frequently running parallel to a street;

- alleyway: a narrow route, often a service corridor originally constructed for the movement of carts;

- footpath: a pedestrian-scale route between buildings, often an ancient right of way and known by a variety of local names such as a ‘loke’ in Norfolk or ‘pend’ in Edinburgh.

The mixture of different types of route within a town, and the way they connect up with each other and to the public squares, expresses the very essence of urban character. Not only is the spatial experience of using them enhanced by their variety and complexity (explore, for example, the Rows in Brighton), but you will often find that key routes have landmarks such as important buildings. These points of punctuation help city dwellers to find their way around and to relate one set of routes to another.

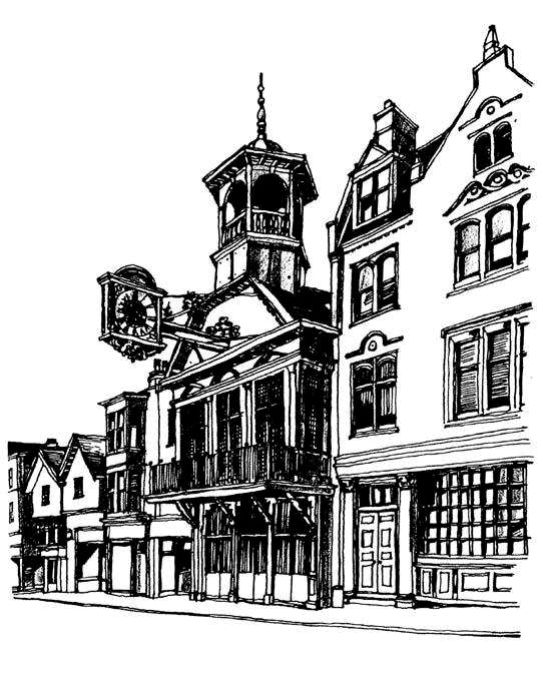

Landmarks along routes come in many forms, from a distinctive ‘event’ such as a decorated pub jutting into the space, to an oriel window overlooking a change of direction, or a lofty church spire. One can search out these ‘highlighting’ features and describe them through the sketchbook. Many major routes through a town are deliberately punctuated by a well-placed statue or public building, but the lesser routes are often accidentally landmarked. Hence a hierarchy of landmarks may exist, each tailored to the scale of the route and its civic status.

If you are intent upon sketching a route, it is important to allow the drawing to focus upon or acknowledge a point of punctuation. Although the sketch may be concerned with the nature of a street or road, the fact that it has a landmark along it that provides local interest should not be overlooked. With long routes the points of punctuation allow us not only to measure how far we have travelled, but to experience the process of movement. On an urban motorway tall or distinctive structures may provide distance markers, and the same is true on a pedestrian-scale alleyway.

Our route along a street can be intentionally punctuated by such features as a clock mounted on a bracket above our heads, or by a colonnaded entrance jutting into the pavement. Such manipulation of our perception by well-placed markers was normally reserved for public architecture, but today it is common to find illuminated advertisements or supermarket frontages exploiting these qualities.

Whether your sketch seeks to analyse a traditional route and its landmarks or a modern one, the same rules apply. Select a good vantage point, compose the drawing in your mind before you begin, ensure the perspective is correctly handled, and make sure the marker on the route is prominently displayed.

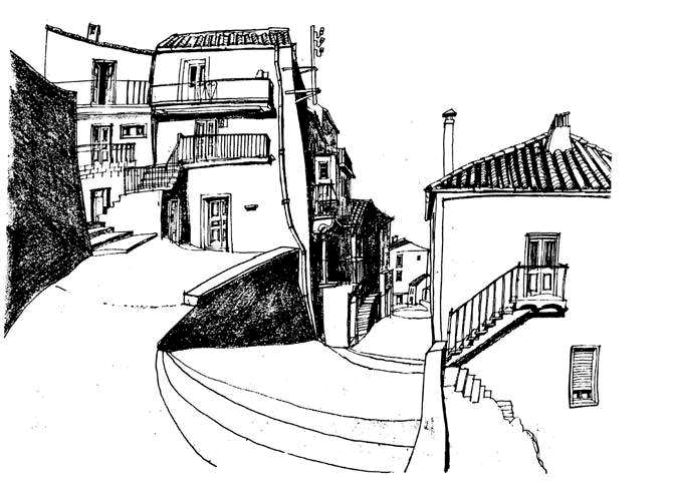

Routes are not only deliberately landmarked, but undergo pleasant changes of direction or level. Frequently a curve in a street is the place to find a distinctive house or shopfront, and at changes of level there may be an old pub or group of ancient trees. Where steps occur they can enliven the scene, especially if there are decorative handrails or lamps to light the way. Search out these incidental events, for they are part of the character of towns and are frequently being swept away or standardised by insensitive municipal authorities.

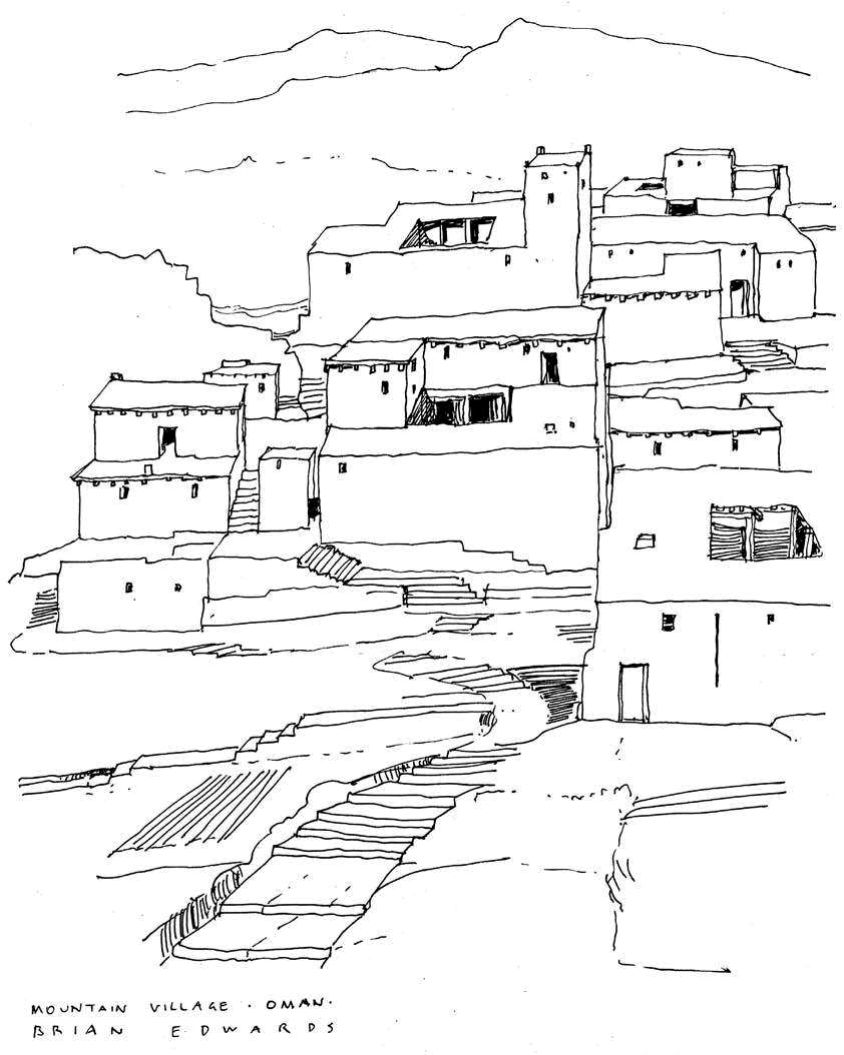

Towns with spatial richness consist of a mixture of the different sorts of streets listed earlier. Generally it is only the bigger cities and those with distinct historical layers, such as Edinburgh, York or Chester, that offer the full repertoire of types of routes situated close together. Other countries are more fortunate – around the Mediterranean it is commonplace to find in quite small places a network of fascinating streets and lanes leading to and from a town square. Here the spatial tensions experienced by the pedestrian are enhanced not only by many changes of level, but also by abrupt alterations of scale as, for instance, a grand central square suddenly opens into view. Added to this, the remnants of fortifications (as in Dubrovnik) provide a perimeter route around the town as well as attractive terminations to many of the alleyways.

Grand cities such as Paris, Washington or Turin contain wide tree-lined boulevards that are rather like linear squares. Here many different types of activity can be accommodated within the broad space of the street – pavement cafés, room for parking, tram routes, through- traffic, central promenades and shaded areas for gossip. Largely the result of nineteenth-century highway engineering, the boulevard sought to bring beauty and ventilation to the heart of congested cities. Today they are worthy subjects for sketching as long as they are treated fairly broadly (attempts to include too much of their detail would defeat the average artist).

For routes to uphold their civic responsibilities they should be legible places: streets need to be landmarked along their route and perhaps terminated at their ends. Yet the enjoyment of towns depends upon a balance between legibility and mystery. The narrow spaces of lanes and alleyways provide mystery and spatial complexity to set against the right angles and open spaces of the major streets and squares. How the parts are put together is largely the result of history – towns normally represent their economic or cultural origins in the present layout of their streets. For the artist, a good street map, a willingness to explore on foot, and the use of the sketchbook as a tool for urban investigation are all equally important. Urban design is best taught in the field, by employing the freehand drawing to record and analyse. Our towns are a shared responsibility – their well-being is momentarily in our hands when we draw and plan them. The much-overlooked visual language of cities resides not only in what we can see and experience from the routes we take, but in how we elect to represent it and thereby protect it.