The Victorian period was the heyday of revivalist architecture, a way of building in which style was a question of reproducing the architecture of the past. The most popular and persistent form of revivalism was the Gothic revival, the imitation of the pointed-arched styles of the medieval churches. The Gothic revival swept across towns and cities because the style was used to build not only churches, but also town halls, schools, railway stations, even factories and warehouses.

In the 19th century Gothic architecture—pointed-arched and stone-built, according to the structural and visual logic of the Middle Ages—made a major comeback. Credit for reviving this more “correct” kind of Gothic goes largely to two architects—Englishman Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin and Frenchman Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc. They looked at Gothic very differently, but their combined influence was enormous.

The work of Pugin

A.W.N. Pugin was a Catholic and is best known today for his work (with Charles Barry) on the Houses of Parliament in London. In 1836 he began a one- man campaign to reform English architecture. Pugin’s big idea was that Gothic represented a culture—medieval Christian civilization—that was far preferable to that of his own time. So in 1836 he published a book with a title that summed up his argument: Contrasts; or, A Parallel Between the Noble Edifices of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries, and Similar Buildings of the Present Day; Shewing the Present- Day Decay of Taste.

In Contrasts illustrations of idealized medieval towns were set next to images of the industrial and architectural squalor of the 19th century. A Victorian poor-house, a building resembling a prison, was contrasted, for example, with a medieval monastery, where comfort and charity were given to the poor. Pugin followed up Contrasts with another book, The True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture (1841). Together, these works set out his big idea: that we should revive Gothic—and, preferably, Catholicism—and improve our social, moral and architectural lot.

The Ecclesiology movement

In the 1830s a number of Oxford-based theologians began to speak out loudly against what they saw to be two threats to the Anglican church—the rise of liberalism and the developments in science that challenged such orthodoxies as the account of the creation in the Bible. They published a series of tracts about their ideas (this led to the movement’s alternative name, Tractarianism) and argued for a church with spirituality and ritual at its center. A parallel movement in Cambridge, known at first as the Cambridge Camden Society and later as the Ecclesiological Society entered the area of architecture head-on, with a series of pamphlets containing clear instructions for church-building. In particular, they recommended that nave and chancel should be clearly separated, with the chancel more highly ornamented than the nave, to enable a proper focus on the high altar. There should also be a vestry for the priest and a porch at the church entrance. Georgian features, such as galleries, were frowned on and Gothic was the style of choice. These recommendations for the Anglican church were very similar to Pugin’s for Catholic churches and together both had a strong influence on the way new churches were built and old churches were restored.

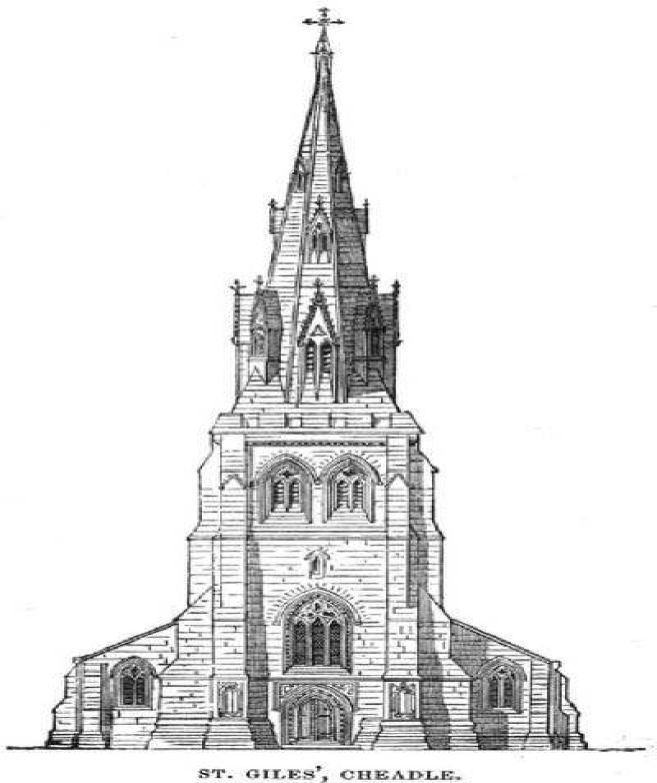

Pugin designed stunning Gothic churches decorated and fitted out in the manner of medieval examples. At their best, as at St. Giles, Cheadle, they glow like jewel-boxes with wall paintings and stained glass. Even Anglicans were impressed. And at the same time the Anglican Church (and its North American counterpart, the Episcopalian) began to make a parallel, if partial, return to medieval values and aesthetics. This happened under the auspices of the Ecclesiological movement, which sought to return Anglican churches to something like their medieval Gothic splendor. British writer John Ruskin, another enthusiastic promoter of Gothic, also had a strong influence on the spread of the style.

“On comparing the Architectural Works of the present Century with those of the Middle Ages, the wonderful superiority of the latter must strike every attentive observer.” A.W.N. Pugin, Contrasts

Viollet-le-Duc

Meanwhile in France, another great writer-architect, Viollet-le-Duc, was campaigning on behalf of a revival of Gothic. His most influential work was Entretiens sur l’Architecture (Discourses on Architecture), which came out in two volumes in 1863–72. Viollet’s emphasis was different from that of Pugin. His great idea was that the Gothic form of structure—with piers, ribbed vaults and buttresses—was a supremely logical way to build that could be adapted with modern materials, such as cast iron.

The result, in mainland Europe, Britain and North America, was a concerted revival of the Gothic style. It was used widely to build new churches for the expanding population, to restore old churches and to build all types of structures, from law courts to railway stations. Major architects embraced Gothic, and this major artistic revival transformed cities from Philadelphia to Paris.

Other revivals

Although Gothic (below) was the most widely revived style in the 19th century, other past styles were reinvented, too. Some saw the round-arched Romanesque style of the early Middle Ages as appropriate as Gothic for churches. It was revived in Britain and Germany, where it became known as the Rundbogenstil (round-arched style). Large country houses were built in every style from Gothic to classical, but a style imitating the heavy forms of Scottish medieval architecture became popular as the baronial style. Later in the century there was a Tudor revival, often incorporating timber-framed gables, that became known as Old English. All these revivals were stimulated by a raft of scholarship about the architecture of the past, published in books lavishly illustrated with engravings.

A varied revival

The buildings these architects produced were hugely varied. While some preferred the ornate Gothic of the 14th century in England, others went for an earlier, plainer version of the style as it first began in 13th-century France. Some were influenced by the Gothic of Venice, which had been vigorously praised by Ruskin. Yet others took the style in intriguing new directions unthought-of by any medieval mason. But whichever type of Gothic they chose, the spires of their churches and the pinnacles attached to their town halls and warehouses transformed city skylines and country landscapes alike.