Sketching may on occasion be supplemented by drawing quick plans or sections. The sketch is a useful and enjoyable tool, but there are occasions when more analytical drawings are required. Although a sketch can indicate the position of a doorway relative to the rest of the façade, it cannot show the importance of the door with regard to the plan of the building. Here you will have to resort to preparing drawings of a more technical nature.

As with sketching, there are a few useful tips to bear in mind. If you are going to measure the subject, get someone else to hold the end of the tape measure, and preferably a third person to read out the dimensions. Your task will then be that of drawing and recording the measurements. Any plan prepared in this way should have the sketch plan, section or elevation drawn at the same time as the measurements are taken, and ideally at the same scale.

Height often poses a problem, but you can triangulate the subject or alternatively use a staircase (if you have access to the interior) to take a vertical measure. Sometimes you can count the number of brick courses, assuming they are laid at four courses per foot. If these fail, then it is possible to take an informed guess on the basis of 9 feet (2.7m) per storey for an ordinary house (allowing for the type of construction) and 15 feet (4.4m) for a grander building.

The sketch plan does not have to be dimensionally accurate to contain useful information. The fact that the building is square in plan, or that a city street is the same width as the height of houses enclosing it, is more important than mere dimensions. You may be able to pace out the dimensions of the building, on the assumption that your step is about 3 feet (0.9m), or determine the height of doors by your reach.

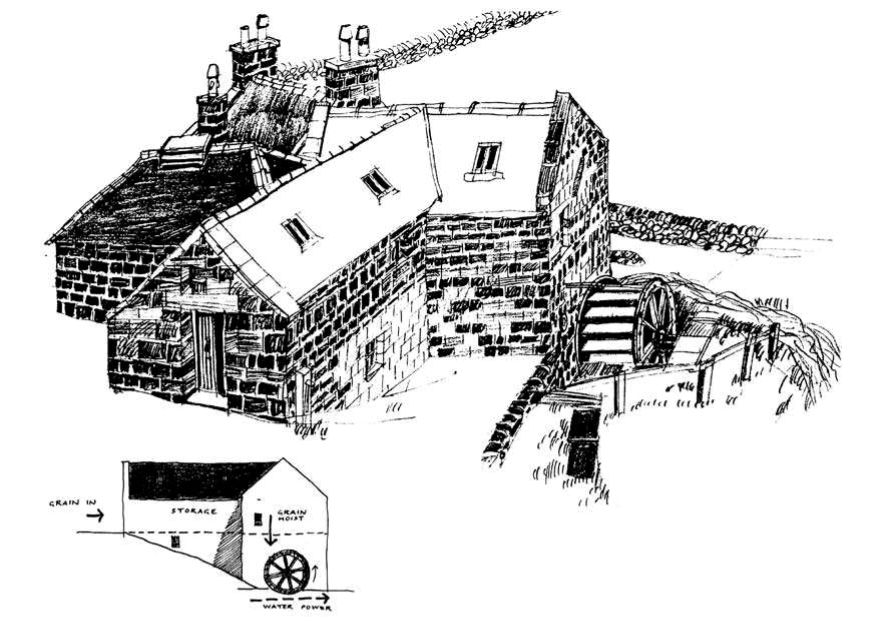

Approximate plans are used to supplement the sketched information and to help bring some aspect of the design into clearer focus. After all, you are sketching to learn about the built environment, and learning does require a disciplined approach. With townscape sketches, a quickly drawn plan of the figure-ground (the relationship between the solids of buildings and the voids of streets and spaces) helps explain the geometry or pattern evident in your view. It may also encourage you to draw from another point in the street, thereby helping you to reach a real understanding of the often complex spatial interactions in an urban scene.

Assuming you have prepared a sketch and supplemented this with a plan or section, then you may decide to take your investigation further.

Local libraries will probably contain documentary records about the date of the subject, or other information that can enhance your understanding of the area you have studied through the sketch. Inquiry through graphic analysis is a useful means of cultivating an appreciation of an area or subject, particularly if it then leads to a search through archival records or historic plans. This may not suit everybody’s needs, but for a school or college project the bringing together of graphic and written sources is a useful educational tool.

Just as in your freehand drawing, the weight of line must be used to help explain aspects of the plan. The sketch plans are meant to communicate and thus should abide by accepted norms of technical drawing. Hence the most important information (such as the position of the walls of a house) should be rendered in the thickest lines and deepest tones. If the garden fence and structural walls have the same weight of line, then their relative importance is obscured. Likewise, the presence of mouldings on the front façade may be important to understanding the proportional rules that the original architect employed (as with a Georgian house), and this fact can be drawn to the attention of the viewer by your selection of an appropriate weight of line. The presence or absence of lines and their relative weight are as important as the presence or absence of words in a report.

Your sketches and plans are really records of facts or your interpretation of them – they are not mere speculations or whimsical invention. If you wish to move into design changes, then your inventions should be clearly indicated. The progression from sketch as record, plan as description, and design drawing as proposed change is an accepted method of proceeding. But it is important that should you mix all three together on a single sheet, then this fact should be communicated to those who look at the drawing. Similarly, records of fact and matters of interpretation should be clearly marked as such and not combined in the same graphic language.

The intention is to supplement the sketch with other relevant information. Your need for additional material will in all probability stem from a practical consideration such as curiosity about how the building is constructed, how the landscape is formed, or the design put together. Hence, the initial sketch – itself probably the result of a need to admire or record – leads to further inquiry that takes you from the sketchbook to the notepad and perhaps to the local archive office, planning department or library. Seen in this way, the sketch is part of the process of understanding, not an end in itself.

Through the sketchbook we may learn to appreciate objects and places for what they are, and as designers intervene in a more informed and sensitive fashion. Because the sketchbook requires our concentrated involvement and can lead outwards into the further investigations mentioned above, it is a great deal more useful than the camera. The camera can only record – it cannot edit, select or interpret. A trained photographer may use the camera creatively, but its educational benefits are limited. By encouraging us to become more visually literate through the countless photographs produced each year, the camera can have the adverse effect of focusing our attention upon the superficialities of subject and form, rather than upon their underlying structure and meaning.