A number of architects have felt the need to counter the “international” aspect of modern architecture. They prefer their buildings to express or respect the place where they are sited, and to draw for their inspiration on local culture. Known widely as regionalism, this attitude has added a richness and variety to the architecture of the late 20th century, and continues to influence architectural thinking.

In writing about the great modern buildings, most critics of the 20th century saw modern architecture as an international phenomenon. Encouraged by the title of the famous New York exhibition The International Style, the buildings of 20th-century “masters,” such as Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe, were treated as a new beginning, as solutions to specific problems rather than responses to local conditions or regional styles. Their favorite materials—concrete, steel and glass—were the same the world over. Modern architecture, in this view, was international, but led by great pioneers from the Western world.

Place and modern architecture And yet these great pioneers did draw inspiration from specific places. Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie Houses, for example, were conceived (and named) as a specifically American kind of dwelling, appropriate to the wide-open spaces of the Midwest. Le Corbusier was inspired by the traditional white houses of Greece. All modern architects worth the name absorbed and transformed influences from specific localities, adapting these influences in the process but leaving some trace of them in their buildings, too.

A later generation of architects saw this clearly. Many of these people came from parts of the world outside the “western” orbit of the early modernists. They wanted to design in a modern way, but to acknowledge the traditions and geographies of their particular parts of the globe and to create buildings that were at one with their setting. Not for them the idea of putting down a modernist steel-and-glass box anywhere, irrespective of climate or local environment. Architectural writers have coined the term “regionalism” for their distinctive and diverse brands of modern architecture.

World-wide responses One place where this can be seen clearly is in the major public buildings of Brasilia, the purpose-built capital city of Brazil. Brasilia’s core was built in the late 1950s under principal planner Lúcio Costa and architect Oscar Niemeyer. Its architecture needed to be at once modern, but also expressive of Brazil’s identity and culture. While designing in a recognizably modernist idiom, Niemeyer introduced the curves of the Brazilian landscape into his buildings. The Chamber of Deputies, shaped like a concrete bowl, the Senate with its white dome and the cathedral with its curving concrete ribs all contribute to this effect.

Other architects engaged on smaller projects also drew richly on regional cultures. The Japanese Kenzo Tange brought together traditional Japanese architecture and modernism. The Mexican Luis Barragán brought to modernism a feeling for color, light and sensuousness that drew heavily on the art and tradition of Mexico. Geoffrey Bawa, from Sri Lanka, developed what has been termed a “tropical modernism” in response to conditions in southern Asia. Hassan Fathy worked with appropriate technologies, such as mud-brick, in his native Egypt.

Regionalism and vernacular

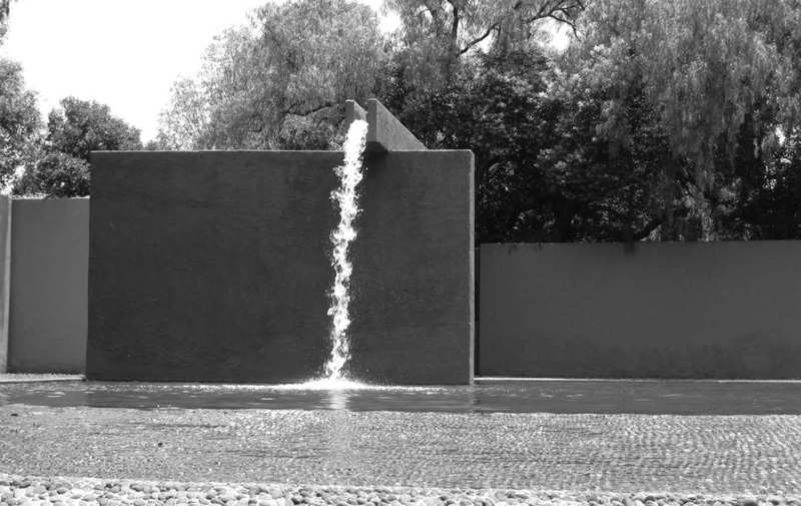

Sometimes planners and architects respond to local building traditions by adopting the vernacular style of the area. This can work, especially when those involved are absorbed in the local way of building and are creating a traditional building type— a house, for example, or a farm building—using local materials. It can also succeed when an architect responds to local traditions, as in Barragán’s work (below). But the mindless imitation of vaguely vernacular styles to disguise buildings such as supermarkets or offices is rarely successful. The form of the building is already decided and designed inside and the vernacular shell acts merely as an inoffensive coating.

Regionalism shines through the work of the likes of Barragán and Tange, but pervades the work of other, less well known architects, too. Even in the West, where commercialism and fashion too often blunt the cutting edge of architecture, practitioners such as Andrew Batey and Mark Mack, working in Napa Valley, California, produce site-sensitive houses of great quality.

“Architecture is a violation of landscape; it cannot simply be integrated, it must create a new equilibrium.”

Mario Botta

These architects and others whose work is inspired by place and locality are a diverse group. They do not constitute an architectural “school.” Barragán, for example, has been called a minimalist (though this belies the richness of his forms and colors), while Fathy’s work is closer to the vernacular architecture of his homeland. But the work of all of them points to something crucial to architecture: that the role of place is central.

Indigenous wisdom It is no accident that many of these architects work in the developing world, where resources are often scarce, technologies sometimes restricted, but local traditions rich and giving. Even in a developed country such as Australia, architects have found much to learn from the landscape and the wisdom of its indigenous inhabitants. Glenn Murcutt, an architect admired for houses that respond well to Australia’s landscape, traditions and climate, has found a way of summing up this position in an Aboriginal proverb. “Touch this earth lightly” is his motto, and his houses, light, open to the breeze, raised above the ground on slender posts, embody these words to perfection.

In the 21st century this message is as important as it has ever been. Every step we take we are encouraged to respect the environment or protect the planet. Buildings make a profound impact on locality, resources and lives, so in architecture above all else it is essential to respect place, as the practitioners of green architecture know. The power of place is still strong.