Western Europe became fascinated with “the Orient” in the late 17th and 18th centuries, as links with China and India became stronger. Few European architects had a deep understanding of oriental architecture, but many were inspired by the details of Chinese and Indian buildings, and used these details as motifs to create deliberately exotic and enticing designs.

For hundreds of years the great civilization of China was little known in the West, but during the 16th and 17th centuries, as Western travelers began to explore the globe, a few Europeans, most of them missionaries sent by the Catholic church, reached China and sent back accounts of the country. Some of these publications, notably the 17th- century Embassy by Dutchman Jan Nieuhof, included engravings of Chinese buildings.

The taste for “the Orient”

These publications fired the imagination of rulers and aristocrats, and one or two of them began to use Chinese elements in their buildings. One of the first was Louis XIV, who in the 1670s built a “Trianon de Porcelaine” with a blue-and-white-tiled roof that does not survive.

The fashion for Chinese buildings caught on more widely in the 18th century, when Chinese porcelain began to be imported to Europe in larger quantities. No doubt a mixture of influences—old books, designs on porcelain, memories of earlier buildings such as Louis’ short-lived Trianon—inspired the Prussian emperor Frederick II when he built his Chinese teahouse in the grounds of his Palace of Sans Souci, Potsdam. This structure of 1757, one of many pavilions in Frederick’s lavish garden, is like no genuine Chinese building. But it has elements influenced by the Chinese taste—columns in the form of palm trees, a roof with slight curves and statues of Chinese figures mark this building out as oriental.

Pattern books

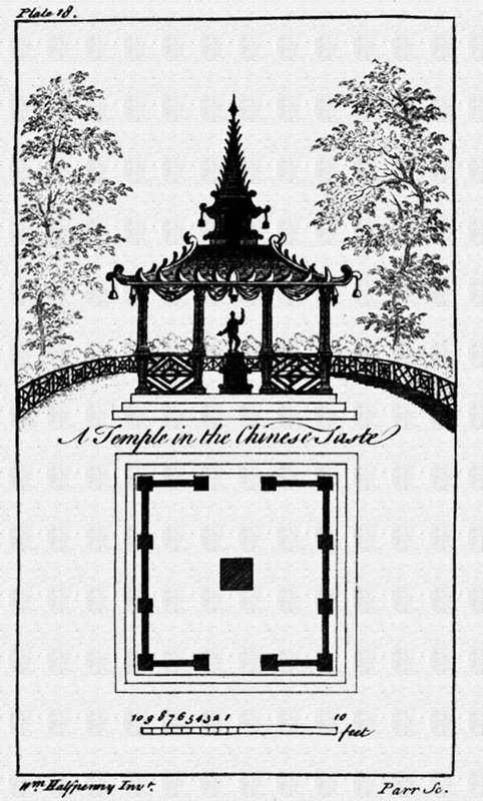

The 18th century was the great age of the architectural pattern book, a publication full of illustrations of examples of architectural details (and sometimes whole buildings), which builders could use to copy or adapt. Many pattern books contained pages of classical details, but some contained oriental motifs. One of the best known was William Halfpenny’s Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste (1750–2), which included designs for doors, gates, bridges and small buildings with pagoda-like roofs (below) and dragon ornaments. Other publications, including William and John Halfpenny’s Chinese and Gothic Architecture Properly Ornamented (1752) and Matthew Darly’s A New Book of Chinese, Gothic and Modern Chairs (c. 1750), also spread the word.

A spreading fashion

During the next 50 or 60 years buildings like this, incorporating elements of oriental style, caught on widely across Europe. A pavilion at Drottningholm, Sweden, and the Palazzina la Favorita, Palermo, are two famous examples. But in aristocratic gardens up and down Europe, many smaller Chinese gazebos and pavilions appeared, and some more adventurous patrons even began to commission interior decoration in the Chinese taste.

“If you have a region of wilderness where you want to build some ethnic dwellings clothed in exotic garb, then the Chinese is sure to be most acceptable.” Prince de Ligne, adviser to Marie Antoinette

Publications fueled the fashion. Sir William Chambers was the greatest, and best informed, advocate of the Chinese style. Unlike any other British architect, Chambers had actually visited China, traveling there several times as a young man when he worked for the Swedish East India Company. In 1757 he published Designs of Chinese Buildings, Furniture, Dresses, Machines, and Utensils. The book contains engravings of various Chinese buildings, including houses, pavilions, bridges, temples and pagodas.

In Britain at this time, most architects looked down on oriental culture. To be a serious architect you were supposed to study classical buildings. But Chambers had the ear of the young Prince of Wales, soon to be crowned as King George III. Soon he was working on the remodeling of the royal gardens at Kew, and building a great pagoda there. The oriental taste was established. Pattern books illustrating garden buildings with upturned roofs, frilly looking decoration, dragon ornaments and fancy “Chinese paling” fences, became popular.

Sharawaggi

This outlandish-looking word, which may come from the Japanese, was first used by a 17th-century writer, Sir William Temple, to describe the asymmetry and irregularity that was such a fetching feature of Chinese garden design. The word became fashionable in the 18th century, particularly when taken up by Horace Walpole, who praised “the Sharawaggi, or Chinese want of symmetry, in buildings, as in grounds or gardens.” Walpole was an enthusiast for the Gothic style, but he liked the playfulness of line, the use of twists and turns, the general irregularity of Chinese design because they were the opposite of classicism. For many, oriental asymmetry was a liberation, and sharawaggi became a cult term of praise when talking about everything from ceramics to buildings.

Other oriental styles

Thanks to Britain’s imperial ambitions, Europe was also discovering the architecture of India. Indian and Chinese styles were frequently mixed and confused. People were apt to refer to pagodas as Indian, or to mistake Indian Islamic buildings for Hindu temples.

The confusion and combination of Chinese and Indian styles reached its peak in the Royal Pavilion at Brighton, the seaside palace designed for the Prince Regent by John Nash in 1818–22. From the outside this building is a confection of onion domes, minarets, openwork screens and other Indian details. It is heavily influenced by Indian Islamic buildings, but with Nash’s own whimsical twist. Inside, however, the decoration is in the Chinese taste, with palm-tree columns and Chinese-wallpaper designs.

The exotic taste

The bizarre combination of styles at Brighton is an extreme example, but it shows how European architects regarded oriental design. They saw the Chinese buildings drawn by Chambers and the Indian architecture described by merchants and officials as sources they could quarry to create an exotic impression. This could be especially effective in garden buildings, where appearance was all. And one or two larger structures, such as Frederick II’s tea house, the Prince Regent’s Brighton Pavilion or a country house such as Sezincote, also made effective use of the oriental mode.