Dutch architects were in the vanguard of modernism from 1910 to the end of the 1920s. Their De Stijl movement, which produced stunning white houses of great refinement, had a strong influence on the Bauhaus and other schools of design, and architects still learn much, both from its careful handling of space and its attention to details and furnishing.

While much of Europe was in the turmoil of the First World War, the Netherlands was a neutral power and the country’s artists and architects took the opportunity to pursue a kind of modernism that was in some ways more refined and advanced than any other. They reduced painting to an arrangement of straight lines and colors and distilled architecture into its constituent parts—planes and spaces. The movement they formed had the simplest of names, reflecting the apparent simplicity of their work: it was called De Stijl, the Style.

“… a style now ripening, based on a pure equivalence between the age and its means of expression …” Theo van Doesburg, printed in the periodical De Stijl

The work of Mondrian

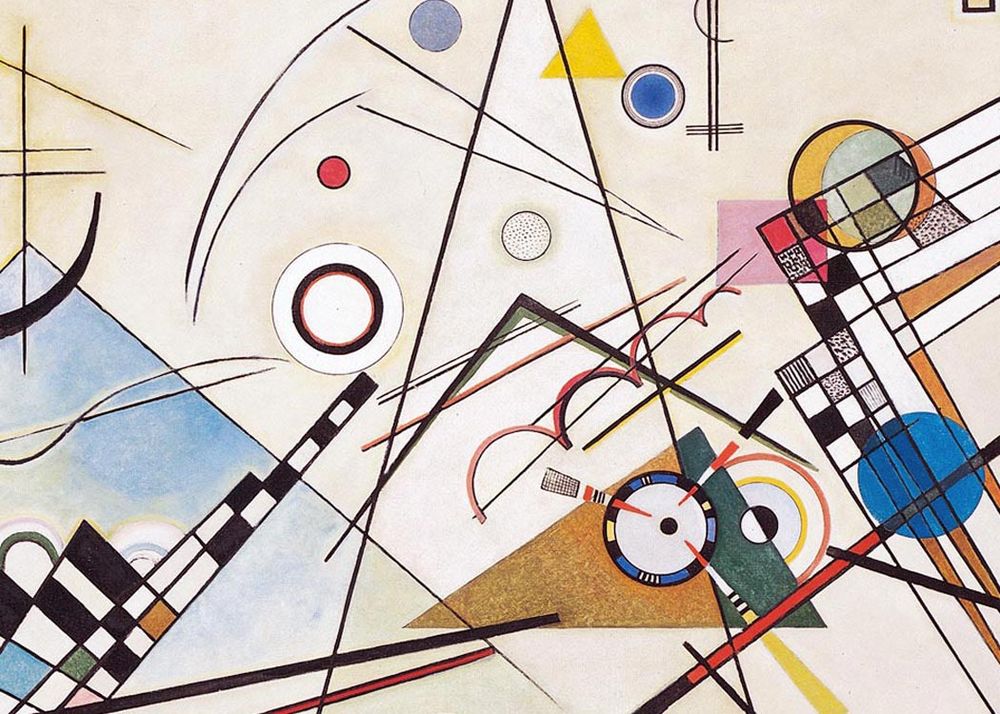

It began with painting, especially with the work of Piet Mondrian. Having begun, under the influence of the cubists, to break down his paintings into arrangements—still representational—of straight lines, Mondrian simplified his work still further. The typical Mondrian canvas consisted of black vertical and horizontal lines, the rectangles between them filled with white or with primary colors. These arrangements had a spiritual significance for Mondrian. As well as breaking painting down to its basic parts, he was also pursuing a higher truth—a type of spiritual geometry.

The influence of Frank Lloyd Wright

Mondrian, a painter, worked in two dimensions. But the artists of De Stijl found three-dimensional inspiration in another source: the buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright in America. The modern Dutch architects seized on Wright’s flair with interlocking planes and fluid interior spaces. They appreciated the big verandas and overhanging roofs of buildings such as Wright’s Robie House in Chicago. And they liked the way Wright designed every detail of his houses. They ignored what was more old-fashioned about Wright— the Arts and Crafts influence and the use of ornament.

Spiritual or pragmatic?

From almost the beginning there was a split in the ideas of the De Stijl movement. On the one hand, van Doesburg, the movement’s great theorist, insisted that architecture should have spiritual meaning. He used elements such as color to build this extra dimension, and saw architecture as a high calling that should take buildings beyond the immediate physical needs of clients. J.J.P. Oud, on the other hand, stressed the importance of the social needs of the people who used his buildings. He left the movement in the early 1920s to pursue his more pragmatic vision, although his houses were still influenced by the powerful composition of De Stijl architecture.

Space and spirit

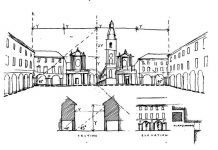

The architect members of the group were Theo van Doesburg, J.J.P. Oud, Gerrit Rietveld, Cornelis van Eesteren and Robert van’t Hoff. They took the pared- down approach of Mondrian, adding the spatial flexibility of Wright. They looked for purity and simplicity of form, but also for spiritual meaning. So a typical De Stijl house is built up of a series of interlocking planes—sections of wall, floor, overhanging roof and so on, mostly colored white but with the occasional dash of pure, primary color. Many of these planes seem to float in space, giving the building an insubstantial quality.

“Masses shoot in all directions—forward, backward, to the right, to the left … In this way, modern architecture will increasingly develop into a process of reduction to positive proportion …” J.J.P. Oud

Inside, there is a free flow of space, sometimes with movable partitions rather than permanent walls between rooms. Large windows help interior and garden spaces meet and blend. Structures such as glass stairs also open up the interior space, as well as giving it a sense of magic. At the same time the strong horizontals and verticals— including glazing bars, balcony rails, and radiator pipes—provide a sense of containment, like the black lines in a Mondrian painting.

Architects’ furniture

Many architects—for example, followers of the Arts and Crafts movement, modernists such as Mies van der Rohe, and members of De Stijl—saw a building as a total work of art. They argued that the architect should design everything in a building, and this included not just fittings but also furniture. As a result many modern architects made striking furniture designs for use in their buildings, and these items also became popular more widely. Mies’s metal-and-leather Barcelona Chair, originally made for the German Pavilion at the Barcelona Exposition and then widely copied, is the most famous example. Gerrit Rietveld’s Red-Blue Chair (see below), a structure of planes and lines like a three-dimensional Mondrian painting, symbolizes De Stijl for many people.

This highly refined type of design reached its most achieved form in the Schröder House, Utrecht, built by Gerrit Rietveld for Mme. Schröder, an artist, in 1923–4. The building is small, but beautifully finished, and the attention to detail is such that most of the fixtures and fittings were designed by the architect himself. The house was furnished with De Stijl pieces, too. The meticulous approach of De Stijl, turning the house into a “total work of art,” worked well with a sympathetic client. But it was less practical for housing schemes for the less well off. But Dutch architects of the De Stijl movement did bring their pure aesthetic to bear on mass housing projects. J.J.P. Oud, a De Stijl member who became Housing Architect for the city of Rotterdam, applied the white-walled aesthetic of simple planes and openings to workers’ housing. His 1920s’ Kiefhoeck and Hook of Holland estates are still widely admired.

The De Stijl movement flourished through the 1920s. Van Doesburg lectured at the Bauhaus (see Bauhaus), taking De Stijl ideas to Germany, from where they influenced architecture as Europe emerged from the First World War and the movement lasted until Van Doesburg’s death in 1931. Today architects still look back to De Stijl for inspiration, and designers admire Rietveld’s furniture designs—reproductions of his famous Red-Blue Chair are still produced.