There is something very distinctive about the grid plans of American cities, but also something limited. At the end of the 19th century a group of American planners tried to open up the grid plan, providing baroque elements such as grand plazas and diagonal boulevards to produce what they called the City Beautiful.

In the 1870s and 80s one of the most successful North American architects was Henry Hobson Richardson. Although he trained at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Richardson’s favorite style was not beaux-arts classicism but a form of round-arched massive style that owed a lot to the Romanesque buildings of 10th- and 11th-century Europe. He designed fine churches and public buildings such as libraries in this style, and his type of architecture, which historians have called both massive and masculine, became popular in the USA, especially in Chicago and the Midwest.

A force for change

But in 1893 a reaction began. This was the year in which the World’s Columbian Exposition was held in Chicago. This was a prestige event, held to attract foreign business to the USA in the wake of an economic depression, and both local Chicago architects and firms from the Eastern cities were invited to design the buildings.

World’s Fairs

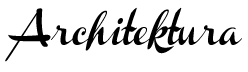

The World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago (below) was one of a number of large-scale international trade fairs held throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. Among the most famous were, as well as the Chicago fair, the London Great Exhibition of 1851, another London exhibition in 1861, the Philadelphia Exhibition of 1876, the Melbourne Exhibition of 1880 and a string of exhibitions in Paris from 1855 to 1900. These were showpieces of manufacturing, promoting international trade. They could also be showcases of architecture, bringing innovative or traditional design to the attention of thousands of visitors. Both the London 1851 exhibition, with its Crystal Palace (see Prefabrication), and the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1889 had famous metal and glass buildings. Others, such as Chicago’s, promoted a grander, more traditional style of architecture.

The overall plan of the Exposition site, laid out by the great landscape architect and reformer Frederick Law Olmsted and the architect Burnham along beaux-arts lines, centered on a “Court of Honor” around a lake. Many of the buildings on the site were classical, lined with columns, and topped with domes. Their stone was mostly white and their elegant, pale, classical appearance soon earned the Exposition site the nickname “The White City.” It was hugely influential, turning many American architects away from Richardson’s ponderous Chicago style to something more classical, and more influenced by the Parisian beaux-arts.

“The civic center’s beauty would reflect the souls of the city’s inhabitants, inducing order, calm, and propriety therein.” William H. Wilson, The City Beautiful Movement

A new approach to planning It was not just the style of the buildings, but the whole attitude to city planning that was affected, in a trend that became known as the City Beautiful movement. Architects and planners had realized that, although American cities generally had grid plans, which in theory could be extended ad infinitum, most had no proper plans for expansion, often no proper city planning at all. The City Beautiful was an answer to this lack.

The planners of the City Beautiful movement proposed to break through the grid plans of American cities with bold diagonal avenues and boulevards, to create dramatic vistas in the grand manner, and to include parks and trees to make the city greener. Planners found an American blueprint for this type of city in the original plan, made by Frenchman Pierre Charles L’Enfant, for Washington D.C. in the late 18th century. This plan, with its treelined streets and rond-points, was followed only loosely, but the City Beautiful planners revived it, aiming to add a touch of the baroque to the grid-based regularity of American cities.

Grand plans

Architect Daniel Burnham was the greatest advocate of the City Beautiful. His 1909 plan for Chicago sees the city sliced through with a series of new diagonal streets converging on a piazza containing the new City Hall. Burnham praised such diagonals as segregating traffic and taking it to the center as rapidly as possible. He also claimed that the triangular blocks created by diagonals were a golden opportunity to design unusually shaped public buildings.

A few American cities, such as Milwaukee and Madison, Wisconsin, were given their share of diagonal streets and grand-manner planning. Some gained boulevards, graceful treelined streets, with tree-planted median strips, often connecting parks and leading out to the suburbs. In these outer areas such streets became “parkways,” genteel streets with views over the landscape. This kind of green planning, already made popular by Frederick Law Olmsted, was also fostered by Burnham and other followers of the City Beautiful movement.

Civic centers

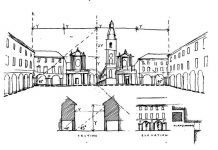

The City Beautiful planners also used diagonal streets to emphasize city centers. Public buildings should be collected together around a central piazza, to which the diagonals unerringly led. There would be public statues and fountains, and the city halls, libraries, museums and other buildings would be arranged around the square in a harmonious way—not just plunked down according to convenience on the grid, as often happened in American cities.

From Elgin, Illinois, to Cedar Rapids, Iowa, many of the plans of the City Beautiful advocates went unrealized. Without supreme power it proved impossible to sweep away city blocks for the sake of vistas in the grand manner. But the idea of a civic center, combining governmental and cultural buildings—something that was achieved in major cities such as San Francisco—had a lasting legacy on American planning, adding beauty and elegance to urban centers, and saying something powerful about what an American city should be like.