The act of drawing is an important starting point for the intellectual process we call ‘design’. To be able to draw a chair or a building is a prerequisite for anyone wishing to design such things. Drawing has two functions for the designer – it allows him or her to record and to analyse existing examples, and the sketch provides the medium with which to test the appearance of some imagined object.

Before the advent of photography most architects kept a sketchbook in which they recorded the details of buildings, which they could refer to when designing. The fruits of the Grand Tour or more local wanderings consisted of drawn material supported, perhaps, by written information or surveyed dimensions.

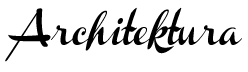

The sketchbook provided a form of research and a library of plans and details to crib at a later stage. Because the architect is not necessarily aiming only at documentary representation, the sketches were often searching and analytical. Many of the drawings prepared found their way into later designs. The English architect C.R. Cockerell used pocket-sized sketchbooks and filled them with drawings not only of sites in Italy and Greece, but also of cities in Britain. His sketchbooks, which survive at the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), show that a direct link existed between Cockerell’s field studies and his commissions as an architect. Later architects such as Alvar Aalto, Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn employed the sketchbook in a similar fashion, though to different ends. Lord Foster (opposite) continues with this tradition.

Drawings have been used by architects in many different ways. Ranging between the opposite poles of the freehand drawing as a record and as a design tool exist many different applications for the designer. Some architects use the sketch as the main means of communicating a design idea to clients. Such sketches relay the thinking behind a proposal as well as suggesting a tangible form. Other architects use the sketch to analyse townscape and to indicate how their design will fit into the street. Others use the sketch as a method of studying building typology, using the analysis as a way of placing their design into known precedents. However the sketch is employed, the main point is to use the freehand drawing as a design tool, as a method of giving form and expression to one’s thoughts. One may finish the design process with a formal perspective, but that end product should not be where sketching begins. Design analysis through the freehand drawing should be at the start of the creative process, not at the end, and preferably before the design commission arrives in the first place. The sketchbook is a personal library; it needs to be built up so that it can become a basis for later, undreamt of, designs.

Many architects’ drawings leave out a great deal of detail. Whether a sketch is of a design proposal or an existing reality, the element of removal or abstraction is one of the characteristics of such drawings. It is better to capture the essence rather than seek an exhaustive realism. Designers need to know what to leave suggested rather than explicitly recorded. The principles and truth that such drawings seek to communicate can be hidden by too much detail or graphic bombardment. A good drawing is one that leaves room for imaginative interpretation. These principles apply equally to a page in the sketchbook or a drawing prepared to highlight a design proposal.

Sketching and freehand drawing have for too long been seen as the point of entry into painting, as against the essential starting point for design. Art colleges have, of course, always maintained a sketchbook tradition among artists and designers alike, but in sixth-form colleges, and even schools of architecture, the sketchbook has been usurped by the computer simulation or verbal description.

The purpose of this site is to revive sketching and analytical drawing as means of understanding form and construction. Only through the study of existing examples – not laboriously drawn but critically examined – can we cultivate a nation of people sensitive to design and its application to our everyday environment. This willingness to learn from past examples should apply across the board, from an appreciation of townscapes to the design of children’s furniture.

Questions of scale are hardly relevant – we live in a designed environment, whether we as consumers are aware of it or not. Every lamp standard and traffic sign has been ‘designed’, the layout of motorway junctions has been shaped by an engineer with an eye to beauty as well as safety. On a smaller scale, our cutlery and crockery are designed, as are the disposable wrappings at the fast- food restaurant.

The sketchbook allows us to be aware of this reality as long as students are encouraged to explore through drawing. The welcome changes to the national curriculum to enhance the status of design and craft teaching, and the broadening of appeal of courses in architecture, landscape design and town planning, have created an unprecedented interest in the environment and design. To turn this interest into a better-designed world requires the development of graphic and visual skills.

In a sense we are all designers, even if we do not make our living through the medium of design. As designers we modify our immediate environment through changing the decor of our houses, or designing our own clothes, to choosing consumer objects on the basis of how they look as well as how they work. We are sold products and services partly by design – you have only to watch television advertising to realise that our aesthetic sensibilities are being appealed to even when the product being promoted is as unglamorous as double glazing.

Prince Charles has awakened the national con- sciousness over questions of urban quality and architectural design. He uses the sketchbook as a means of describing and understanding the places he likes. The sketch is employed as a learning tool rather than as mere description.

The untrained eye can learn a great deal through drawing. It teaches an important visual discipline – an awareness of shape, line and perspective. The sketch also engenders respect for the environment and the designed objects within it. To have sat for an hour and drawn an old panelled door is to create a respect for the object that may discourage the tendency to daub it with graffiti, or to relegate it to firewood. Such doors could be recycled if their qualities or beauty were respected, and the sketch rather than the instantly obtained photograph is the means to this awareness.

It is said that in our modern world we now produce more photographs than bricks. For the first time in history the visual image has become more prevalent than the means of making houses. The lesson concerns the importance of design and appearance in contemporary society. But photographs are not always the most appropriate medium for expressing this visual concern. There are times, and subjects, which lend themselves to graphic analysis, rather than pictorial description.

This site aims to of reviving the sketchbook tradition, in order to create a visually literate society. The objective of education is to achieve not just literacy and numeracy, but graphic, visual and spatial skills. Our success as an industrial society requires this; and so do we, whether as designers or as individuals.

If this site inspires people – professional designers or otherwise – to explore the environment round about them with sketchbook and pencil (as against camera) in hand, then a useful beginning would have been made. There are always subjects to learn from, whether we choose to live in city, suburb or countryside. This book takes themes based upon everyday experience, and seeks to draw design lessons from them. Once we have learnt the language of drawing and graphic analysis, we are then in a position to engage in the complex business of design.

For the first time in history design involves us all and has permeated through to every aspect of our lives. If we ignore the language of design, we will be as disadvantaged as those who finish school without the basic skills of literacy and numeracy. No single book can teach us how to learn through drawing, but it can point us in the right direction and open our eyes to the benefit of good design.

TYPES OF DRAWING

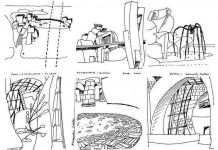

To the architect and urban designer there are three main types of freehand drawing. The first is the elaborate perspective drawing used to communicate design ideas to clients or planning authorities. Increasingly this type of drawing is produced by computer. The second type concerns the production of sketch perspectives and views used to communicate design ideas to specialists such as engineers, and sometimes to help clarify points for the designer’s own benefit. This type of drawing can be split into:

- the investigation of an early design;

- exploring methods of construction;

- testing the visual effect of details;

- setting the design in its physical context.

The third type of freehand drawing concerns the exploration of the existing world, its buildings, details and landscapes. The use of drawing in this regard does not just provide a repertoire of forms and designs to use in developing new structures, but helps cultivate a sensitivity towards the existing context in which architects, planners and landscape architects are increasingly required to work. Of these three broad categories of drawing, this book focuses upon the latter.

With a growing awareness of the cultural and aesthetic values of cities, and with the European Community requiring ever-higher standards of urban design, those in the environmental professions face new challenges.

The general public, too, are better informed and through local amenity societies and bodies like the National Trust make their views known on an unprecedented scale. The widening of education to embrace design and technology (under the national curriculum reforms of 1990) promises to focus yet more attention upon design in public fields such as architecture. Hence the world of the professions has been opened to challenge by an informed public, with design no longer the monopoly of people with letters after their names.

Before the modern design professions were established, students and practitioners employed the sketchbook as a matter of course. They were not topographical artists but people in search of creative material. The Arts and Crafts architect George Devey studied under John Sell Cotman in Norwich in the 1830s, thereby absorbing not just Cotman’s approach to freehand drawing, but a whole collection of details of windmills, barns, country houses, castles and cottages which later proved invaluable to Devey the architect. Similarly, Richard Norman Shaw, Ernest George, John Keppie and, later, Edwin Lutyens continued to use the sketchbook to record the towns and buildings not just of Britain, but of Europe and the Middle East. One can trace the origins of the architectural sketchbook back to the Renaissance, but its blossoming as a creative force in its own right owes much to the nineteenth century.

The sketchbook is a personal record – a dialogue between artist and subject. The nature of the dialogue determines the quality or use of the finished drawing. By engaging in the subject, the artist, architect or student develops a sensitivity and understanding difficult to obtain by other means. The blind copying of subject is not necessarily useful – a critical stance is required. One may never use the sketch produced of the town or landscape – at least not directly – but, like reading a good book, the insights gained may prove invaluable later on.

The designer needs to be accomplished in the three main areas of drawing mentioned earlier. To be able to render a convincing perspective is an essential skill; to explore the detailing of an unbuilt structure through sketches avoids pitfalls in the final design; and to use freehand drawing to learn from past examples helps the architect or urban designer to give better shape to townscapes of the future. The environmental awareness that is a feature of our post-industrial society has encouraged a return to questions of firmness, commodity and delight. These are the qualities the Arts and Crafts architects sought to discover through their sketchbook investigations. This book seeks to pick up the threads of a drawing tradition, and to use them to teach us lessons about the contemporary city, its buildings and landscapes.

DRAWING TODAY

Drawing is a technique that allows the visual world to be understood. It is a convention, based upon a degree of abstraction and analysis, which focuses the mind upon aesthetic values. Whereas numbers are useful to economists, words to politicians and poets, lines are what artists and designers employ. Visual literacy is developed through the medium of drawing.

A distinction needs to be made between drawing as a tool for designers and drawing as a technique employed by artists. Although both artists and designers use drawing to help develop ideas, they do so in quite different ways. Artists are concerned with mark making, rather than descriptive drawing, and such marks are usually the genesis of later inspirational work. Their drawings are invariably abstract and experimental even when based upon observation. Even when fine art conventions are followed, the drawings made by artists tend to be fairly free form, employing mixed media and integrated with other visual material such as photography or collage. Fine art drawings, as against the drawings designers make, are likely to employ scraffitto (texture), impasto (surface), and shade (light and dark to give the effect of modelling). Designer drawings, on the other hand, employ a more mechanistic response based upon disciplined observation of what is before the observer. This is not to suggest that architects’ drawings are without abstraction or inspiration (although it is often sadly the case), rather it serves to remind society that designers solve both visual and functional problems through the medium of drawing. Their drawings contain the genes that allow future objects to be designed, made or built. In this sense the freehand drawings of architects and designers are not only anchored in the context of the present but contain the fertile possibility of the future.

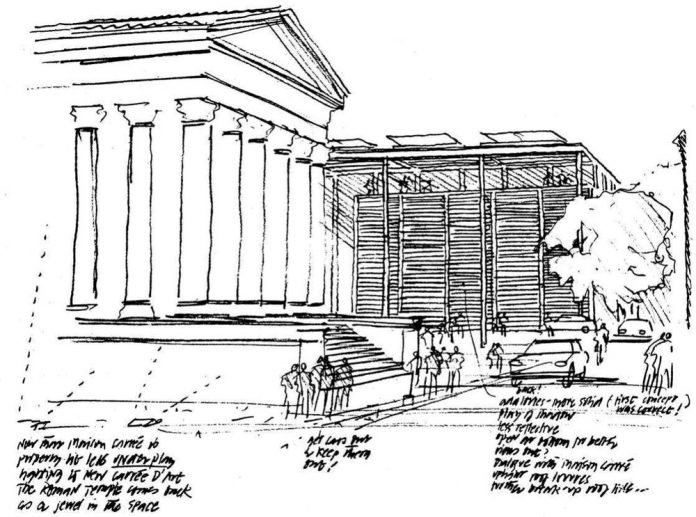

To help architects understand form certain con- ventions have been developed. These include ortho- graphic projection and perspective drawing, both of which have had their potential greatly amplified by computer- aided design (CAD) graphics. The combination of two- and three-dimensional drawing techniques means that a typical architect or product designer employs a mixture of plan, section, elevation, axonometric and perspective drawings to communicate their intentions. Increasingly these are all packaged into a CAD programme using AutoCAD, ArchiCAD or similar graphics software. What this book is mainly concerned with, however, is the stage before formal drawing begins – those preliminary sketches often made in the field or studio that help to develop visual awareness. These early sketches, placed for convenience in a sketchbook, allow precedent to be understood, methods of construction to be analysed, relationships in space or time to be assessed, and much more. For the designer the sketch is less an experimental beginning based upon abstract concepts (although this may be the case in the work of Zaha Hadid and Frank Gehry), and more the critical examination of a building, place, landscape or programme. The architect generally builds his or her designs upon precedent. Even the best architects learn from the example of other architects’ buildings, and often from their own. Many cultivate an awareness not just of contemporary precedent but historic examples too. Certain architects also seek to understand and exploit types of precedent drawn from outside the world of the built environment. For example, Norman Foster admits to being influenced by the design of airport hangars and the aircraft themselves, whilst Santiago Calatrava is inspired by structures and designs found in nature, especially the shape and construction of bones. In both examples, sketches are used to learn about physical, material and visual properties – ideas that then migrate into their architecture.

Design is ultimately about solving problems. The future exists as an imaginative idea within the mind of the architect. Translating this concept into a building requires drawings. The problems to be solved are functional, technological, environmental and social. How sketches and more formal drawings are employed by architects varies but generally speaking sketching occurs at the beginning of the process, with two-dimensional drawings (such as plans) being utilised more towards the end. The first sketch made is instrumental and tells us a great deal about how a designer thinks. If the early design sketch takes the form of a section, the final building will be quite different had it been a plan. Likewise, had the first sketch been of a historic building of similar type, or of the structure of the landscape, or of some abstract but related concept, the final design again would have proceeded in a quite different fashion. For example, the architect Will Alsop often begins his design process with a painting that embodies some of the abstract ideas that more formal drawing may eliminate. His paintings are colourful, joyful and rich in design potential. Another architect, Edward Cullinan, carefully draws the visual relationship between his site and the wider city or landscape. In the process he discovers new ways of solving the design problem – ways that subtly stitch the new building into the wider scene. With Cullinan, as with Foster, the focus and tension in these early sketches informs the whole design process.

The type of drawing employed reflects well the intellectual inquiries undertaken by the architect. The plan is often the primary generator but sometimes the section or orthogonal projection takes priority. Sketches are explorations of spatial or formal possibilities. However, ideas are not only worked out in drawings, models and increasingly paintings are also employed, especially by those architects who are under the influence of art practices. More adventurous architects, from Rem Koolhaas to Zaha Hadid, use diagonal rather than orthogonal projection, creating dynamics in section as well as plan. When the lines are then stretched and twisted, the resulting buildings have a richness that the obsessive use of the right angle tends to deny.

Architects uniquely have invested in them the shaping of the future of cities. They shape this visually, functionally and socially (the latter in collaboration with town planners). Architects are essentially artists working at the scale of the city and with the material of building. Like other artists, they engage in shape, colour, light and space – manipulating all four to solve technical and aesthetic problems. Although architectural design is anchored by function to the reality of everyday life, architects are responsible for the evolution of buildings as cultural icons. They shape cities by looking sim- ultaneously at precedent (with the sketchbook) and forwards to some unknown future (with CAD). As such, the freehand drawing is not part of a dead tradition but of a lively and inventive future. In this sense also the sketch is not made redundant by CAD but complements it. The two together provide architects with powerful tools to design the future. However, to ignore the act of drawing and to over-rely upon mechanical aids is to undermine any shared values between artists and architects.