In the last few decades of the 18th century a new attitude to the ancient remains of Greece and Rome began to emerge. Archaeologists and architects began to record these buildings more meticulously, making and publishing measured drawings that had a huge influence, bringing a new type of classicism into fashion in Britain, France and America.

The influence of Andrea Palladio transformed the architecture of Europe, bringing classical architecture to places such as Britain (see Palladianism). But Palladianism was a very particular type of classical architecture, based on the ideas of a 16th-century Italian rather than on the buildings of the ancient world. In the mid 18th century a group of architects began to look further back in time for their inspiration in a bid to create architecture based not on the buildings of the Renaissance, but on those of antiquity— ancient Rome and ancient Greece.

Buried cities unearthed

They were helped in this by the rise of a new discipline, archaeology. In the 1730s and 1740s people saw some of the most dramatic of all archaeological revelations—the lost Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum, buried beneath the volcanic debris of Vesuvius, began to be unburied.

Suddenly, modern scholars and artists were closer than ever before to the Romans themselves because the excavations famously revealed not just buildings, but also the actual people, the petrified imprints of their bodies as if frozen in time. In addition, importantly for architecture and the decorative arts, remains of wall paintings, furniture and other domestic items brought people closer than ever to the way the Romans arranged and adorned their homes. The quality and number of discoveries stunned the world.

Etruscan style

Another influence on interior decoration in the late 18th century was the painted pottery unearthed in the ancient Greek world. Much of this was thought to be Etruscan, so the 18th-century decorative style using a similar palette of black, terracotta and white also became known as Etruscan. Pale, cameo-like figures on a darker ground were also used. Robert Adam was an exponent of the style, as was the Frenchman François-Joseph Bélanger. The famous Jasper Wares produced by the British potter Josiah Wedgwood were also influenced by this Etruscan style, and Wedgwood named his factory “Etruria.”

Recording antiquity

Meanwhile two British architects, James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, spent three years in Athens in the early 1750s measuring and drawing many of the ancient buildings. They took the fruits of their work back to England in 1755 and, after a long delay during which Stuart bought Revett’s interest in the drawings, the first volume of The Antiquities of Athens was published in 1762. Three further volumes appeared over the following decades, the last in 1816. The work of Stuart and Revett was but a major part of a wider movement. Several volumes on Roman antiquities, including Charles-Louis Clérisseau’s Antiquities of Nîmes (1778), also appeared.

Although neither Stuart nor Revett designed many buildings, their publication made them famous, especially Stuart, who earned the nickname “Athenian” Stuart. But one very active and successful architect followed in their footsteps, making and publishing accurate drawings of ancient buildings, the Scotsman Robert Adam. Adam traveled to Italy in search of Palladian inspiration, but he met Clérisseau and the two men traveled together to Split in Croatia to make measured drawings of the enormous palace of the emperor Diocletian. The drawings were published in 1764.

“…we flatter ourselves, we have been able to seize, with some degree of success, the beautiful spirit of antiquity, and to transfuse it with novelty and variety, through all our numerous works.” Robert Adam, preface to The Works in Architecture of Robert and James Adam Esquires

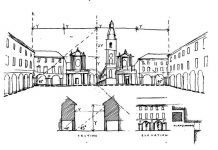

So during the second half of the 18th century, architects and clients, especially in Britain, became aware for the first time of the exact details and proportions of the buildings of ancient Greece. Their knowledge of the Roman world was also enhanced. This was true especially of Roman domestic buildings—hitherto temple architecture had been the main source for architects; with the excavations of Pompeii and Adam’s work at Split much more was known about Roman houses and palaces.

Robert Adam

This work had a huge impact on architecture. Adam’s delicate style of interior decoration, for example, owes much to his studies of Roman wall-painting, but also draws on Greek motifs, such as vine patterns, and ideas about the artistic style of the Etruscans.

At Syon House in Middlesex, he even incorporated genuine ancient Roman marble columns, hauled out of the River Tiber, into one of the interiors. These stunning columns are adorned with capitals inspired by Greek architecture and topped with gilded statues of the type the Romans might have placed on a triumphal arch. Adam, though influenced by scholarship, was not afraid to mix up sources in order to create a dramatic effect.

Neoclassical motifs

A number of motifs were widely used by the architects and decorators of the 18th century and became closely identified with classicism. These include the interlocking “Greek key” design (below), the palmette (a palm-leaf design) (below) and the anthemion (a plant motif similar to the flower of the honeysuckle). The palmette and anthemion often appear together, alternating in a frieze.

Neoclassical forms

Adam’s genius, so often called on to remodel country house interiors, brought out the decorative, filigree aspects of ancient architecture, the aspects that could be expressed in paint, plasterwork, gilding and the occasional marble column. Other architects drew more closely on the actual form of ancient Greek and Roman buildings. Thomas Jefferson, for example, designed the library of the University of Virginia at Charlottesville in the form of the Roman circular temple the Pantheon, a shape also adopted by the architect Georg von Knobelsdorff for the Catholic church of St. Hedwig in Berlin. French architects, such as Etienne-Louis Boullée and Claude- Nicolas Ledoux, took neoclassicism in a different direction (see Reason), radically extending its forms.