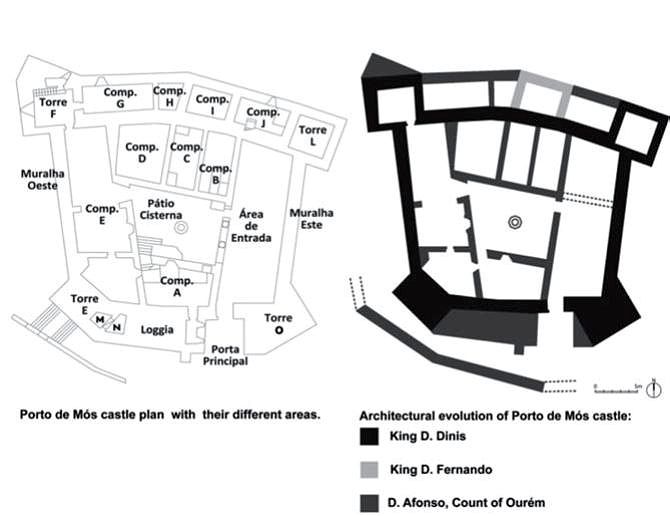

Articulated with the neighbouring villages of ourém and Pombal, Porto de Mós played a strategic role in the defence of the important cities of leiria and coimbra since medieval times. In the thirteenth century, under King dinis, the castle acquired its relatively regular shape with four towers, which was the basis of subsequent reforms, such as the fourteenth-century addition of a fifth tower, by King Fernando. The last major construction campaign that added a palace to the castle took place in the mid-years of the fifteenth century and is due to afonso, fourth count of ourém and putative heir to the duke of braganza.

While the exact date of afonso’s campaign is not known, most of the works must have taken place after the count’s return to Portugal from his second trip to Italy, in 1452, since they included innovations of an experimental character that originate there. On the one hand, they introduced new military features to the castle including openings for firearms. On the other hand, they increased the available liveable space as well the residential character of the castle through the addition of tiled roofs rising above the battlements and new (as well as novel) loggias.

The interior of the building was subdivided and much altered, maintaining a small distribution patio followed by the main courtyard around which a series of new chambers is organized. new features reflecting increasingly sophisticated notions of comfort were also added such as fireplaces, and large windows and loggias providing striking views over the surrounding landscape. In order to understand the resulting fortified palace, one must take into account afonso’s cosmopolitan life and his long voyages in europe, especially in Italy. After the works due to him, the palace of Porto de Mós reflected the most advanced european innovations in both military and residential architecture of its time and could not be rivalled by any of its other Portuguese counterparts.

THE CASTLE

The castle of Porto de Mós is located in the Portuguese region of estremadura and was built on a hillock, 176 m high, to make optimal use of the topography of the land. Its foundation in the twelfth century fits within the general context of the christian ‘reconquest’ and the maintenance of new territories. Together with the castles of ourém and Pombal, it had an important strategic role in the defence of the cities of leiria and coimbra. However, it was only in the early thirteenth century, during the reign of King dinis, that the castle acquired its main layout, possibly reusing built structures of previous reigns.

The original plan of the castle was adapted to its geographic location. The small size of the hillock hindering the use of a large area, the castle adopted instead a small and irregular pentagonal form. As was customary, it was organized around a small courtyard that could accommodate a small military garrison and some supporting infrastructures, allowing for a maximization of the castle’s defensive capabilities.

The castle was defended by four towers erected on the four corners of the structure and protruding outwards from the wall, which allowed defending the base of each tower from the top of the next one. Possibly, these works were made after King dinis donated Porto de Mós to Queen elizabeth of aragon, in order to provide the fortress with better facilities for its new status. In subsequent years, we find once again an information gap on the architecture of this castle until the reign of Fernando I, in the fourteenth century.

The new king, according to the chronicler Fernão lopes, after the funeral ceremonies of his father Pedro I, retired to the castle of Porto de Mós and made his first decisions as king there, including a major reconstruction programme of Portugal’s fortifications. This reference is important, as it acknowledges that the castle of Porto de Mós already had physical conditions to house a monarch. Thus, it is not surprising that in 1387 it could be called a ‘paço’, a palace.

It was possibly in the course of these actions that a fifth tower was built in the north wall, which was thus reinforced at the pentagon’s edge. this hypothesis fits within the political and social context and is reinforced by the analysis of the wall in question, which seems to present a small rupture to fit the new structure. In any case, all of the architectural elements mentioned so far fit within the building paradigm of the ‘gothic castle’.

After these works and still during the reign of King Fernando, the building suffered some damage from the wars with castile and during the crisis of 1383-5, and it seems that this damage was only repaired in the mid-fifteenth century, when the fourth count of ourém decided to intervene in the old defensive structure.

FROM CASTLE TO PALACE

The starting date of the great enterprise undertaken by afonso, count of ourém, is unknown. However, the renovations of the castle were perhaps carried out after the works which the count commissioned at his other palace of ourém, and possibly after the battle of alfarrobeira in 1449, extending through the following decades. Among his many journeys, the count of ourém had travelled to Italy in late 1451 where he remained during the first half of the following year.

Much of the work was probably done after his return. Contrary to what he did in ourém, in Porto de Mós the count did not order the construction of a new palace, but instead decided to change the existing building. This decision may be connected to the impossibility of building a new structure given the available area and to the fact that the extant structure already presented some features of habitability and comfort.

Nevertheless, its reconstruction was quite extensive and altered the face of the enclosure in order to provide the old fort with residential conditions worthy of its new owner. The reconstruction programme improved the existing structure’s organisation, proportion and balance, in a very ingenious project that ultimately did nothing more than fill and reorganise the available indoor space and, on the outside, compose the facades, in a way that corresponded to the ‘educated forms’ of the Italian renaissance that were influential all over europe during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Throughout the fifteenth century, Porto de Mós no longer endured any effective military threat. Nonetheless, it continued to be an important marker in the landscape and a symbol of an emerging and dominant ‘lordly’ power. This village can be considered the birthplace of the house of ourém, since it was in this castle that the troops of nuno Álvares Pereira (afonso’s grandfather) were stationed before the battle of 1385 after which he was honoured with countless lands, including the village of Porto de Mós.

In addition to a strong symbolic dimension, surely felt by afonso, these lands were also an important element of luxury, status and socio-political assertion by the new house of ourém, whose head aspired to being regarded as the new constable of the Kingdom and to achieve ‘visibility’ within the royal circles. This could explain why the military function of the castle was side-lined, though not neglected.

Alongside this fact there is the episode of intrigue with the infante Pedro in which the count of ourém watched over the castles of Porto de Mós and ourém against the infante Pedro, in his retreat in the ducal lands of coimbra. The mid-fifteenth-century reconstruction works provided the pre-existing structures with some innovative elements of military architecture, albeit in a somewhat experimental way. The wall-walk was kept on all towers and walls, supported by a set of very long pyramidal corbels, elements that, like merlons, can be seen as a symbol of nobility.

In addition, a new defence system was adopted for the main entrance, which was protected from above by two machicolations and laterally by two very basic embrasures, simple conical openings, accommodating artillery. Embrasures were also added to the north-east corners of the towers e and F, to protect the vulnerable castlefront facing the river ; here the slope was less steep and easier to climb, and it was indeed from this side that the castle had been assaulted at its first conquest in 1148.

Porto de Mós’ main gate, facing the village, was protected, during the fourteenth century, solely by two towers, framing the gate. The door itself was further reinforced by several mechanisms, including its bolting with two wooden bars at mid height and a vertical shutter closing it from the inside. This structure was possibly remade by afonso, as shown by the mason’s marks. On the outside of the fort, a small part of a barbican could still be seen in the 1940s. barbicans, which functioned as the first obstacles to be encountered by the enemy, became widespread in Portugal after the middle of the fourteenth century and throughout the fifteenth century, and this solution was also applied, it seems, in Porto de Mós under the supervision of afonso.

However, whether this was an extensive barbican surrounding the whole fortress, as was the most common formula, cannot be confirmed. Construction works included a strong consolidation of the pre-existent structure; almost all towers had their corners reinforced through the incorporation of well-carved cornerstones in limestone, which possibly means that parts of the towers were rebuilt in this period. This is also suggested by the distribution of the different mason’s marks. There are 39 identified mason’s marks, most of them attributed to the period of afonso, scattered throughout the entire fortress. Although aristocratic residences in the late Middle ages sought a certain visible prominence through the incorporation of military elements, they also sought to make their spaces increasingly more comfortable.

For this purpose, very broad changes were made to the existing building. Prominent among these was the addition of two great structures, one in the south front (between towers e and o) and the other in the north front (between towers F and I and I to l), thereby increasing the available living area so as to improve the residential potential of the fortress. In each of these areas new compartments were created, opening onto a loggia. The one facing south, towards the village, is organized in four bays with rib vaults and heraldic keystones, supported by corbels with vegetal decoration, a model which, according to josé vieira da silva, had first been introduced in Portugal by master huguet in batalha.

tural evolution. Source: adapted from architectural surveys made by dgeMn.

This loggia connects the inner space to the outer landscape through finely decorated windows with four countercurved arches resting on thin octagonal columns. Flanking the loggia are two balconies, the one to the west supported by six staggered modillions, the one to the east by four. They both look as if designed to protect the large span created by the loggia. For the same purpose a new body was also added to tower F, creating a triangular edge, which is repeated in towers e and o (the latter absorbed by the south loggia). It creates a constructive pattern that is repeated throughout the building and in the organisation of the indoor space of the towers.

The inside of the building was also subdivided and extensively modified through the maintenance of an entrance area and the construction of new compartments (a, b, c, d, and e) around the courtyard which, like the classic house model, appears to organise the circulation, providing access to the new quarters of the ground and upper floors. To access the latter, there was possibly a stairway, located roughly in the same place as the current one, starting next to the door of compartment a, where there is a massive block of stone, and turning south separating compartment a from e.

This structure would be supported by the visible discharge arc inside these compartments. However, this central area probably underwent reconstruction as well, since in the previous centuries there must have been compartments here, some of which were destroyed or integrated in the new structure. The spaces of the upper floors are currently undocumented. However, we do know that the nobler areas were heightened when compared with some tower floors, as can be seen in the loggias and in the window of the west wall. Most of the stairways were possibly built in stone.

On the other hand, all these spaces, in line with the classical decoration of the patio, from which the columns and fluted pilasters with Ionic capitals remain, probably presented different decorative architectural elements. This is confirmed by the fragments of the frieze with geometric decoration that were found during the restoration works of dgeMn and by later archaeological interventions. These compartments (a, b, c, d, and e) seem to belong to the count of ourém’s campaigns, not only because of the architectural features that unify them, such as the vaulted ceilings supported by corbels and the design of the doorframes similar to those found in the palace of ourém, but also because they all present shallow foundations and thin walls.

Furthermore, within compartment b, the remains of a silo filled with spoils from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries have been discovered; the upper part of the old silo was undoubtedly destroyed when the count built the new compartment. The castle’s roofing is an interesting result of this fifteenth-century campaign. Different kinds of roof were used to cover the building. The towers were probably crowned by spires covered with scaled tiles, similar to the present state of the south-west and south-east towers (the result of restoration works in the 1940s). These roof tiles are glazed in green, the colour of the house of ourém.

The shape of these roof structures is unknown, but domestic and foreign parallels, namely French, suggest they may have been conical or quadrilateral. As stated by alexandra barradas, by the end of the fifteenth century the castle of Porto de Mós could compete with the state-of-the-art in europe. It had been updated through the introduction of military technical novelties and an Italianizing taste, resulting from the count’s many travels, including the use of the courtyard for organising the space, the jagged lintels on the doors, the columns and the pilasters, and the machicolations crowning the towers and walls.

As for the cistern courtyard, analysis of the stone work and its decorative elements seems to confirm the hypothesis of rafael Moreira, who suggested that the fourth count of ourém may have hired an Italian craftsman – a scalpellino or marmorano – for their execution. This exogenous taste was wisely combined with forms of the late gothic and with distinctively ‘national’ features, as exemplified by the castle of leiria, the convent of tomar and the monastery of batalha. With the latter, aside from the undeniable stylistic influences, there was possibly a shared use of craftsmen; perhaps officers and craftsmen working in batalha also intervened in the Porto de Mós building site. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that similar mason’s marks are found on both buildings.

Another common element is the stone used in both buildings, since the quarries of Porto de Mós are known to have supplied the construction site of batalha. Surely afonso, lord of the region, ensured for his own work the same raw material that was supplied for the royal enterprise. The collected data does not allow to determine with certainty the functionality of the different compartments of the castle and its final form before the interventions of dgeMn. But the remaining documentation informs us that a prison was located inside the castle. The enhancement of the residential function of the castle is also apparent by the introduction of new elements, concerned with the comfort of the space.

In Porto de Mós, in addition to the loggias, large windows of noble appearance were opened, with their pointed arches providing light and ventilation. Moreover, seated in their ‘conversadeiras’ (stone window seats) facing the outside of the building, those who lived in the castle could enjoy the outdoor scenery. This feature present in the remodelling works of afonso, is found in the west wall and in the top floor of each tower, where large windows emerge facing the outside, organised in a rhythmic and harmonious way.

Another important element found in this castle, that once again suggests the notion of convenience, is the existence of a brick chimney and the attending fireplace framed in stone on the third floor of tower F. This not only provided greater comfort by keeping the room warm, but was also a symbol of social status. Reflecting a growing concern in palatial buildings of this period, the castle also includes features related to water and hygiene. There was a cistern, for instance, which provided autonomous water supply. Considering its architectural features, the cistern dates from the fifteenth century, and was possibly also introduced by the count of ourém.

This is not surprising if we add the important and exquisite piping system that spreads throughout the building and interconnects with the new constructions. Finally there are also two compartments that can be considered dumps or evacuation sites (M and n). These two structures possibly received waste from different areas of the castle, channelling them by gravity beyond the barbican, a steeper area, distant from the castle, since there is not a flowing water line that could do it. However, the water intake and conveying system would be much more complex.

In sum, the castle of Porto de Mós under the aegis of d. Afonso was given new defensive systems, but also elements that enhanced the comfort and luxury that the residential building needed to house its new lord. Its appearance would have been quite elegant and sophisticated as the count of ourém brought to this building the knowledge and the taste of his cosmopolitan life and long stays in european countries, especially in Italy, which he wisely managed to combine with the best made in Portugal. As written by a. de almeida Fernandes: ‘the good repute of the house was that of its owner.’