The development of innovative technologies opened up undreamt of possibilities for the creation of space and building in architecture. However, despite the enormous transformations in the economic and social spheres of highly industrialized countries, the architecture of the late 19th century still used the means of expression deriving from previous epochs.

With the ubiquitous eclecticism of historical styles it had lost creative character and authenticity. Many architectural historians discuss the problem of paradoxical dissonance between industry, academic tradition, and everyday life. Well, the dynamic development of industrial cities and changes in the way of life in the machine era required a definite change in the expression of architecture and art.

In a strongly hierarchical society, the principles adopted for the construction of bridges and factories could not be applied to prestigious public buildings, and even less so in the private residences of wealthy entrepreneurs. In addition, the academic traditions developed in previous epochs guarded the classical orders of architecture. Such an attitude was shared by the majority of professional and cultural elites.

The establishment of 19th-century engineering as a distinct discipline from architecture, confirmed by the opening in France of the L’École Polytechnique, was a sign of progress. On the other hand, the exclusion of structural and technological problems from the area of architecture, and the detachment of academic teachers from the practice, led to an ossified system of teaching focused on the problems of composition and the harmony of forms and proportions.

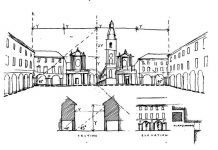

The L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the most influential architecture school in Europe at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, had a strong impact on design practice. It dictated quality standards and determined the canons of beauty. Meanwhile, the architectural design process was brought back to the development of plans with multi-axially symmetrical patterns of abstract but unfunctional elegance.

A few such designs, for example, the prestigious Prix de Rome National Bank project by French architect Tony Garnier, a graduate of L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts, awarded in 1899, show how far the teaching in this university corresponded with the requirements of the industrial era. The confining of an academic world to its own circle, isolated from the technique, led in the 19th century to a clear division between the art of decorating and art of building.

This was reflected in surprising definitions, such as by Gilbert Scott: “Architecture is unlike regular construction in that it is a decoration of the construction“ and Edwin Lutyen: “Architecture starts where the function ends”; “Unlike regular construction, it is a decoration of the structure”; “(it) starts where the function ends.”

The effects of such a division were evident in the superficiality of the architecture of the 19th century – the insincere decorative appearance, the disappearance of the relationship between the façade and the structure, the interior and the exterior, and the structure and the form; generally, the destruction of the organic traits of buildings. Reducing the tasks of architecture to mere aesthetics decreases the scope of the problems addressed to style issues.