The Bauhaus was a school of design, founded in Germany in 1919, that had a lasting influence on architecture and the design of all types of product. Its creator, Walter Gropius, aimed to marry good design with the use of machines for manufacturing and the adoption of modern materials in architecture. His methods were widely copied, and several Bauhaus designs became classics.

The Arts and Crafts movement of the late 19th century had encouraged a coming-together of all types of artists, designers and craft workers to create everything from jewelry to buildings by marrying a revival of traditional craft methods to a clear analysis of form and function. Arts and Crafts architecture, though less cluttered than the Victorian work that preceded it, still looked traditional and rooted in history. What if the ideals of good construction and close cooperation between artist, architect and artisan were focused on more modern, more industrial design?

From Werkbund to Bauhaus

One answer to this was provided in Germany by an organization called the Deutsche Werkbund. Founded in 1907 in Munich, the Werkbund brought together a group of cutting-edge designers and artists who focused on designing without looking to past styles for inspiration or imitation. The group created pioneering work in design and architecture, but was not radical enough for one young architect, Walter Gropius, who wanted to move closer to industry and industrial design. In 1919, therefore, Gropius made a career move to become head of a school of arts and crafts in Weimar, which he reorganized and renamed the Bauhaus.

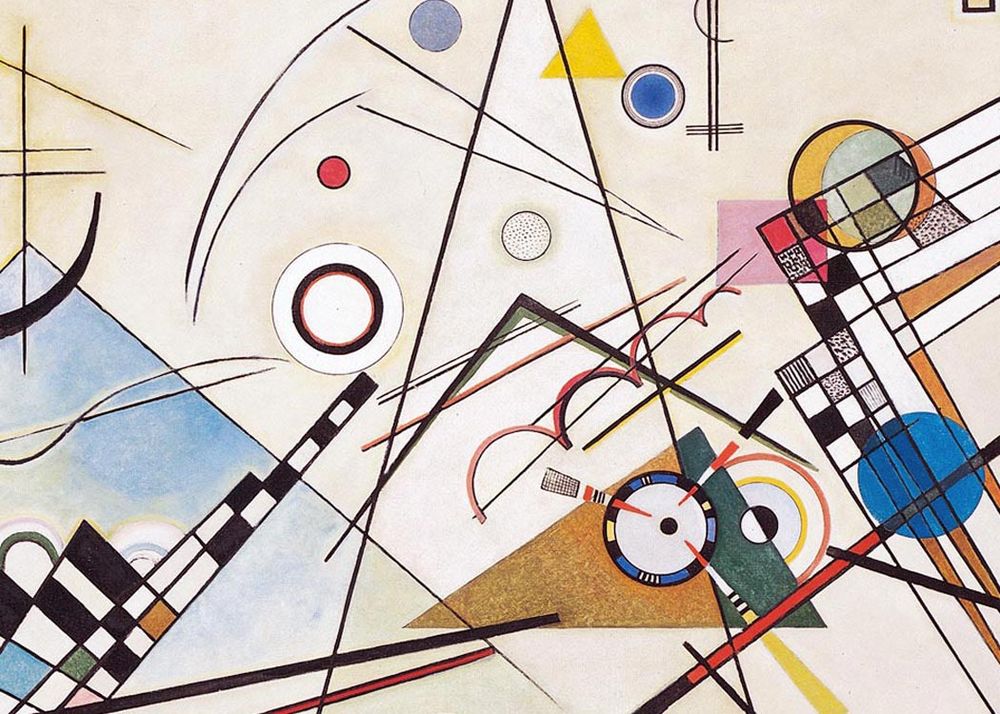

Gropius wanted to bring industry and craft closer together, to revolutionize how things are designed and made. He saw that in order to do this, he had to educate students not only in craft and design, but also in concepts such as form and color. So he added a group of painters to the staff of the Bauhaus, men such as Paul Klee and Johannes Itten.

The introductory course

Itten was especially influential because Gropius put him in charge of the Vorkurs—an introductory course taken by all students when they arrived at the Bauhaus—in which these key concepts of form and color were explained. Students then went on to learn both how to make designs of objects—both for mass production and for one-off production but still in a “machine aesthetic”—or to design buildings. Gropius championed the modern approach to architecture—exploiting both the strength and visual qualities of materials such as steel, concrete and glass and rejecting what he saw as the “dishonest” claddings and trickeries of 19th-century architecture.

“The Bauhaus believes the machine to be our modern medium of design and seeks to come to terms with it.” Walter Gropius, Idea and Construction, 1923

The move to Dessau

When, in 1924–5, these ideas proved too radical for the backers of the Bauhaus in Weimar, Gropius moved the school to Dessau, building a striking new headquarters that, with its pale concrete walls and large windows, exemplified Bauhaus ideas. This was where some of the most famous products of Bauhaus design were created: Marcel Breuer’s tubular steel and leather armchairs and Gropius’s light fittings in glass and chromium, for example.

The Bauhaus building

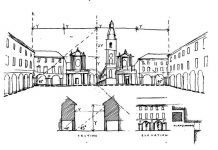

The building that Gropius designed for the Bauhaus at Dessau (below) is one of the most important of the 20th century, embodying several architectural ideas that were to be widely imitated and adapted. It was planned as a series of blocks, each with a different function—one containing teaching rooms and library, one workshops and studios, another student accommodation. These blocks were linked by a section containing a lecture hall and a bridge housing the administrative offices. This zoning, with each block expressing in its outer appearance the rooms within, was highly influential, as was the fact that the resulting plan had no “front,” just a series of wings. The freely designed spaces, the frank use of concrete and steel, and the strong straight lines were much copied, both in educational buildings and more widely.

The architectural impact of the Bauhaus also increased, as Gropius won commissions to design housing projects such as workers’ housing for Siemens outside Berlin. In such schemes, as well as capitalizing on the standardization offered by using modern materials, he tried to bring air and light into his houses, to make them more attractive to live in than traditional or 19th-century dwellings.

Gropius, and the directors who succeeded him, Hannes Meyer and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, did much to promote the values of modernist architecture through the Bauhaus, while also keeping alive the modernist version of the old Arts and Crafts ideal—that every object in the home, from crockery to curtains, should be well designed. This holistic approach is one of the most important legacies of the Bauhaus ideal.

Closure and emigration

The Bauhaus was strong, but could not resist the rise of Nazism with its very different ideas about design. Hitler was interested in expressing the German character through traditional classicism, and saw little merit in modern design or its practitioners. So in 1933 the Nazis closed the school.

But in some ways this increased the influence of Bauhaus ideas. Most of the staff emigrated to the USA, where they continued to promote their type of design and where artist Lázló Moholy-Nagy briefly set up the New Bauhaus in Chicago. In the 1950s another stalwart, Swiss architect Max Bill, took Bauhaus ideas to the design school at Ulm, bringing this type of design back home once more. As a result the products of the Bauhaus, from modernist chairs to steel-and-glass buildings, are well known all over the Western world.