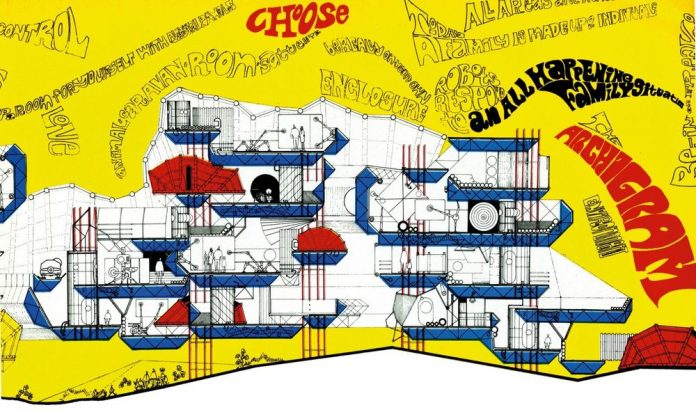

The British group Archigram formed in the 1960s as a forum for architectural discussions and ideas. Its projects existed mainly on paper, but its ideas were highly influential. The members of Archigram preferred popular culture to the heroic high-culture of modernism, and proposed an architecture in which there were no buildings in the conventional sense—instead there were plug-in modules and adaptable, disposable structures in bright, Pop-Art colors.

The avant-garde architectural group Archigram flourished in London during the 1960s. Archigram was a rich mixture of people—of the main six, three (Warren Chalk, Dennis Crompton and Ron Herron) were experienced architects whose designs had been built, and three (Peter Cook, David Greene and Mike Webb) were young, inexperienced and full of not always practical ideas. This combination of experienced practitioners and bright young ideas men produced a unique mix, able to think in new ways and propose radical design directions.

Tech and pop

The architecture of Archigram took its inspiration from the latest technology: spacecraft, oil rigs and underwater structures. They were also influenced by contemporary culture: pop art, comics, the Beatles, throwaway packaging. Architecturally, they were interested in the lightweight structures of the American Buckminster Fuller (see Dymaxion design), as well as in the ideas of the futurists, who saw cities as machines.

Bowellism

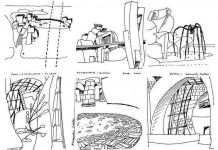

In 1958 the architect Mike Webb, soon to be a member of Archigram, designed a project for a headquarters building for the Furniture Manufacturers’ Association. The proposed building, which looked like a collection of gigantic tubes, cylinders and containers, was all curved corners and rounded walls. It was the most famous design of a lost architectural movement, which, because its buildings resembled human intestines, became known as bowellism. These curvaceous forms, although unbuilt, were influential in 1960s’ design and in the way in which high-tech buildings sometimes displayed the “guts” of their structure on the outside.

This extraordinary mix of characters and influences led to an architecture in which the conventional distinctions could be broken down. Archigram conceived megastructures, but not in the form of skyscrapers or the “heroic” structures of modernism. Among their most famous ideas was the Walking City—a structure that looked like a giant insect on metal legs. Turning inhabitants into nomads, these walking communities could stop at service stations where they could stock up with supplies. They were also designed to provide a protected habitat in the event of a nuclear war.

Another Archigram project, the Instant City, was more a happening than a structure. It would arrive—drawings show it carried by hot-air balloons—in a drab town and stimulate it with the addition of performances, structures and new technologies. This instant stimulation, it was argued, would awaken potential intelligence and creativity in the community, and local people would then be hooked up to new networks, leaving a grid of connected communities in place after the traveling circus of the Instant City had moved on.

The modular city

Plug-In City proposed a vast framework into which could be fitted countless standard “modules.” Put simply, this sounds like an extension of existing ideas about prefabrication. But Archigram took the notion much further, and much deeper. One way in which they proposed to do this was in the field of transport. They were dissatisfied with trains and petrol-driven cars, which they saw as smelly, dangerous and demanding of space in the form of tracks and roads. They saw an alternative in the form of the electric car, which was clean and compact. They tried to treat it as a mobile piece of furniture, integrating it with buildings in a way that was impossible with conventional vehicles.

Archigram turned many accepted notions upside down. Houses were replaced with living pods with curved, organic forms, or with portable dwellings, or with suits that contained a life-support system. Buildings moved, or grew, or were turned inside-out. It seemed to be a world of infinite possibilities and of optimism about the possibilities offered by technology.

“To see architecture as much the natural outcome of circumstance as any other product or situation is an extremely healthy attitude.” Peter Cook, Experimental Architecture

A means of communication

The group’s ideas were highly influential, in part because the members of Archigram were good publicists and teachers. They published their ideas in a broadsheet (itself called Archigram), which sold all over the world. Illustrated with bold, comic-like drawings, these publications were a breath of fresh air.

The group also found vocal supporters in critics such as Rayner Banham who publicized their ideas still more widely. The architect Hans Hollein, who contributed to some of the Archigram publications, saw the power of all this writing and drawing when he described their architecture as “a means of communication.”

Skins

Many Archigram structures took a kind of organic form. “Living pods” had curved sides and ceilings; Walking Cities resembled insects; cylinders and other rounded forms abounded in their work. Many of these structures were covered with “skins” of various types, evoking the use of new materials in architecture—canvas, plastic or glass fiber. These were lightweight coverings, a far cry from the heavy and solid materials, from concrete to timber, used in most buildings. But some architects and engineers took them up and made innovative structures with them. Frei Otto’s stunning tent-like structures for the 1972 Munich Olympics (see below) are famous examples.

A lasting influence

All the writings and drawings brought Archigram great respect among other architects. Although their drawings and Pop-Art-inspired ideas have a strong period flavor, their ability to think in different ways contains lessons that go far beyond the 1960s. They had a powerful influence on the hi-tech movement. Their creative way with frameworks and “floating” service structures left its vivid mark on buildings such as the Pompidou Center in Paris. And their ideas continue to be examined by architects into the 21st century who want to look at their practice in new ways.