In the 1870s a number of landlords and social reformers began to design improved housing for ordinary people, creating spacious settlements with generous gardens that became the first “garden suburbs.” At the end of the century this idea was developed and extended into the garden city movement, with the creation of entire new towns that had a lasting influence on the way housing developments were planned.

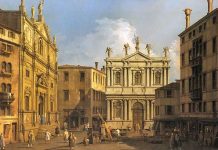

The movement began with the garden suburb, an idea that has its roots in the Arts and Crafts movement and in the “Domestic Revival” architecture—a mixture of Tudor, vernacular and Queen Anne—of the 1870s and 1880s. An early example was the West London suburb of Bedford Park. Begun in 1875 Bedford Park was a series of treelined streets meeting at a village center containing the station, shops, inn and church. There was plenty of greenery and the houses had large gardens. The houses themselves—many of which were designed by Norman Shaw—combined red brick, timber and inventive elevations with bay windows, porches and other interesting details—in other words they were the essence of the style that came to be known as Queen Anne.

Other communities along similar lines appeared, most notably Bournville, the industrial garden village built by the Cadbury chocolate company for their employees. While Bedford Park, with its mainly large houses, was emphatically middle class, Bournville cast its social net more widely, with accommodation for workers on different levels of the Cadbury’s hierarchy. The place grew, too, with more houses and buildings, such as schools and churches, being built in the decades after its foundation in 1879.

The social mix

Pioneers such as Ebenezer Howard saw themselves as social reformers. They wanted to improve people’s lives and create better societies by planning suburbs and cities in innovative ways. They encouraged such beneficial activities as getting out in the fresh air and growing vegetables in the garden. They also tried to promote a good social mix, providing houses of different sizes, so that rich and poor could live close by, as they tend to do in a city center.

The vision of Ebenezer Howard

Settlements such as Bedford Park and Bournville influenced the pioneer planner Ebenezer Howard, but his vision was larger. He wanted entire cities to be built on these principles, with generous planting, plenty of space and community facilities. He wanted something else, too: a type of planning logic that reflected his values of community. Howard was convinced that garden cities were the cities for tomorrow.

In 1898 Howard published his ideas in a book called Tomorrow; a Peaceful Path to Real Reform. The book was reprinted four years later under the title Garden Cities of Tomorrow. Howard was convinced that both town and country had their attractions and wanted to bring both together in a new type of city. It would be as pleasant to live in as a garden settlement, such as Bedford Park or Bournville, but because it was a city it needed to be larger and contain community facilities, such as museums and libraries, a hospital and a town hall. And because Howard could see clearly the advantages of keeping city and country in close proximity, the garden city contained not only parks and gardens, but also, on its edges, allotments and dairy farms, with larger farms just beyond its edges.

The English House

The skill of British builders in creating well-designed housing for all social classes impressed the government in Prussia so much that they sent the architect Hermann Muthesius on a factfinding tour to the country in the 1890s. Muthesius studied all types of houses, large and small, but was especially impressed with the architecture of Bedford Park (see below) and Bournville. He included examples of both in his long, three-volume study, Das englische Haus (The English House), which appeared in 1904–5 and immediately became a standard work on English domestic architecture. The book helped spread the ideas and aesthetics of British housing into mainland Europe.

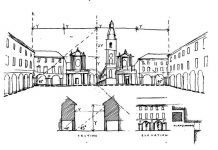

The concentric plan

Howard laid these diverse elements out in a circular town plan that was both beautiful and logical. At the very center was a garden, from which a number of boulevards radiated, like the spokes of a wheel. In a circle around the garden were the major public buildings—town hall, concert hall, theater, library, hospital, museum—and in a broad ring around them was a large, central park. Concentric rings of avenues containing houses and schools followed, and beyond them were a railway line, allotments and dairy farms.

Greening the city

Howard’s design was revolutionary. Most city dwellers at the end of the 19th century had to put up with cramped conditions and treeless streets. Howard’s proposed city would give them a sense of space, greenery and state-of-the-art public facilities. But in the Britain of the late 19th century the emphasis was on adding to existing towns rather than building entirely new cities, so there seemed little prospect that Howard’s vision of tomorrow would ever be built. Garden cities were built in Germany, though. Hellerau, which was begun in 1907 near Dresden, and Neudorf, Strasbourg, begun in 1912, were notable examples.

“Twn and country must be married, and out of this joyous union will spring new hope, a new life, a new civilization.” Ebenezer Howard, Garden Cities of Tomorrowo

In Britain, two new towns drew on Howard’s ideas: Letchworth, begun in 1903, and Welwyn Garden City, laid out in the early 1920s. Letchworth—with its curving streets, neo-Tudor houses and greenery—is close to Howard’s ideals and to the principles of developments such as Bedford Park. Welwyn is planned along similar lines, but by the time it was built the neo-Tudor style had been replaced by a type of imitation Georgian.

The ideals of Howard and his ideas lived on—not in further new towns, but in countless estates and suburbs built on to existing cities. Curving streets and closes, green spaces and neo-Tudor or neo-Georgian houses proved a winning formula for the large amounts of social housing that were needed after the Second World War. Developments such as these from the 1920s and 30s still prove popular with tenants and planners alike.